Responding to Adversity

Everybody encounters adversity at some point in their lives. This could include a traumatic experience, childhood deprivation, poverty, chronic illness, a sensory impairment, brain injury or dementia. Each type of adversity can impact on psychological wellbeing and cognition, cascading to all aspects of life.

A critical barrier to supporting each person who encounters adversity is that everyone responds in a different way. We want to address this by understanding the social, environmental, cognitive and neurobiological factors that drive this variability. We believe this is necessary for us to develop novel interventions that support long-term recovery across different adversities and clinical scenarios.

Our Research on Responses to Adversity

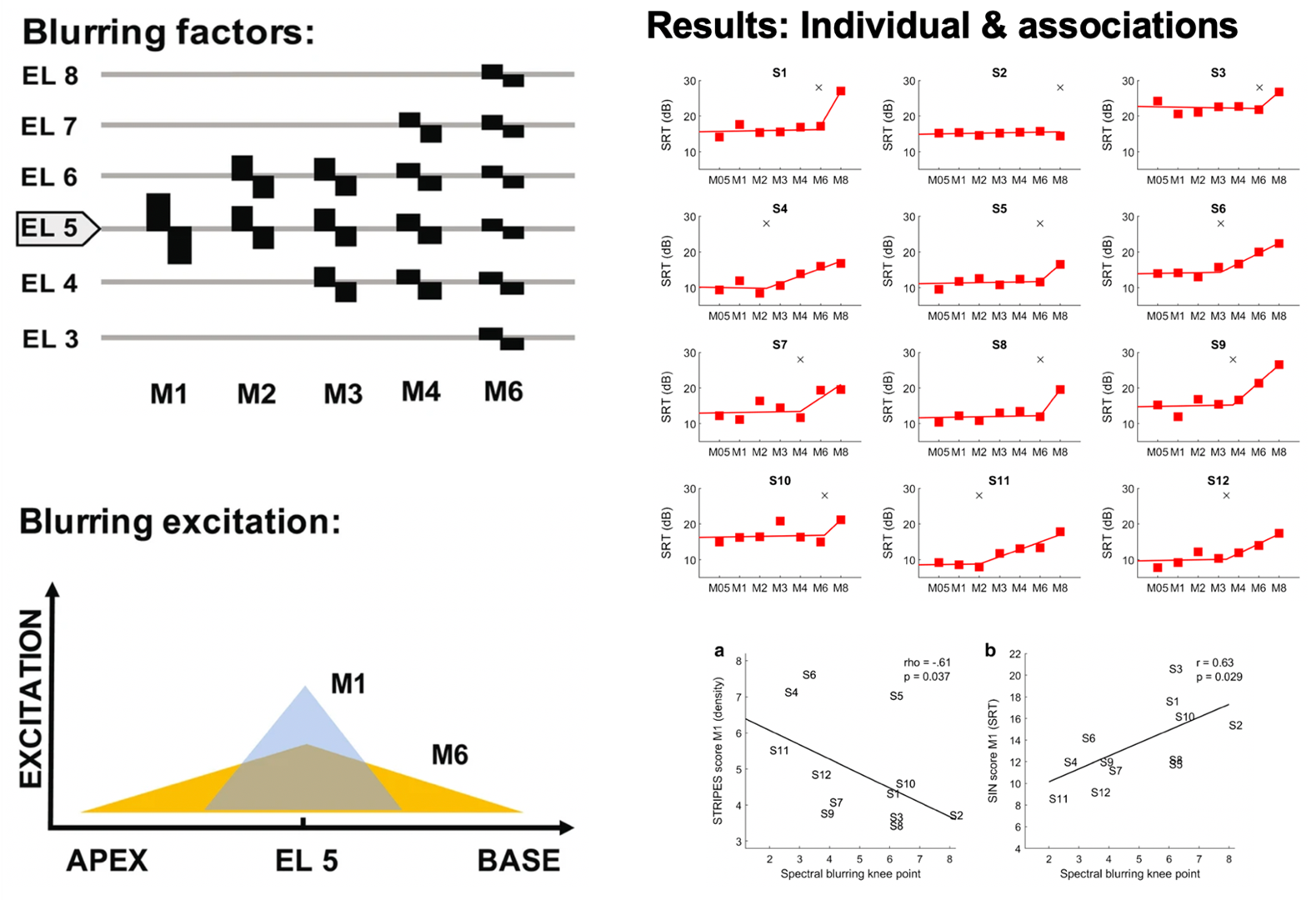

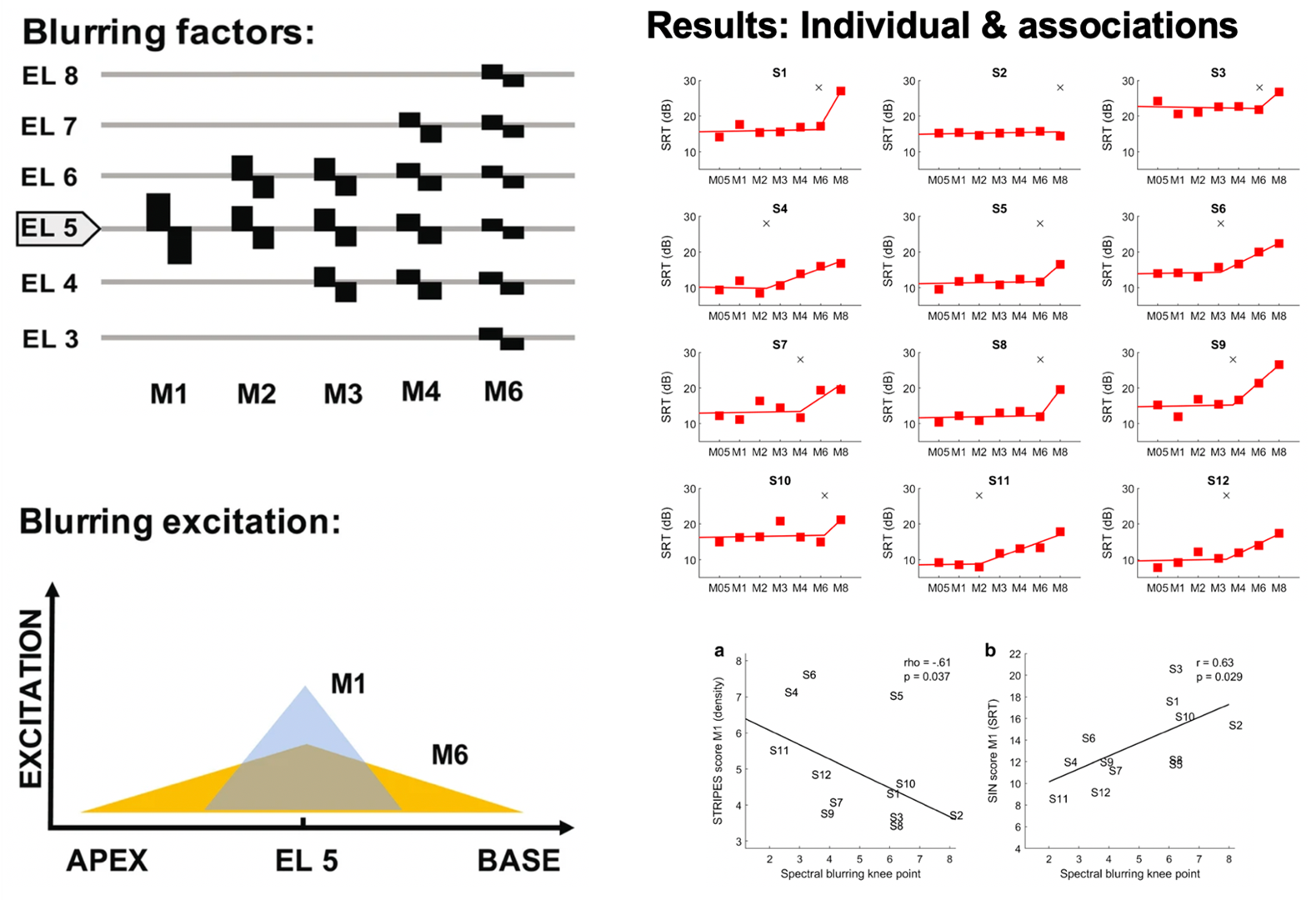

Cochlear implants (CIs) are neuroprostheses that can provide good speech perception in quiet listening situations, but often fail to do so in environments with interfering sounds (e.g. in a restaurant or classroom). Importantly, there is a lot of variability between CI listeners, and it remains unclear why some people do really well with CIs, while others struggle a lot more. Previous research suggests that this is due to detrimental interaction effects between CI electrode channels, limiting their function to convey frequency-specific sound information, but evidence is still scarce.

We developed a method to directly investigate the effects of channel interaction in CI listeners. We used an experimental manipulation called spectral blurring to measure causal effects of channel interaction and found that it affected speech perception, but only when all channels were blurred simultaneously or when the most-apical (low-frequency) channels were blurred. Importantly, the amount of spectral blurring leading to changes in speech perception differed between individuals and was associated with their listening profile, indicating that channel interaction directly explains some of the variability between CI listeners.

This research provides insights into individual difficulties and differences between listeners. Further, the idea behind spectral blurring to assess causality rather than correlation can be used to disentangle the contributions of CI-, cognitive- and language-related causes. This could in future be used to develop tailored interventions for individual listeners based on their requirements.

Citations

GOEHRING, T., Arenberg, J. G., & CARLYON, R. P. (2020). Using spectral blurring to assess effects of channel interaction on speech-in-noise perception with cochlear implants. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, 21, 353-371.

GOEHRING, T., ARCHER-BOYD, A. W., Arenberg, J. G., & CARLYON, R. P. (2021). The effect of increased channel interaction on speech perception with cochlear implants. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1-9.

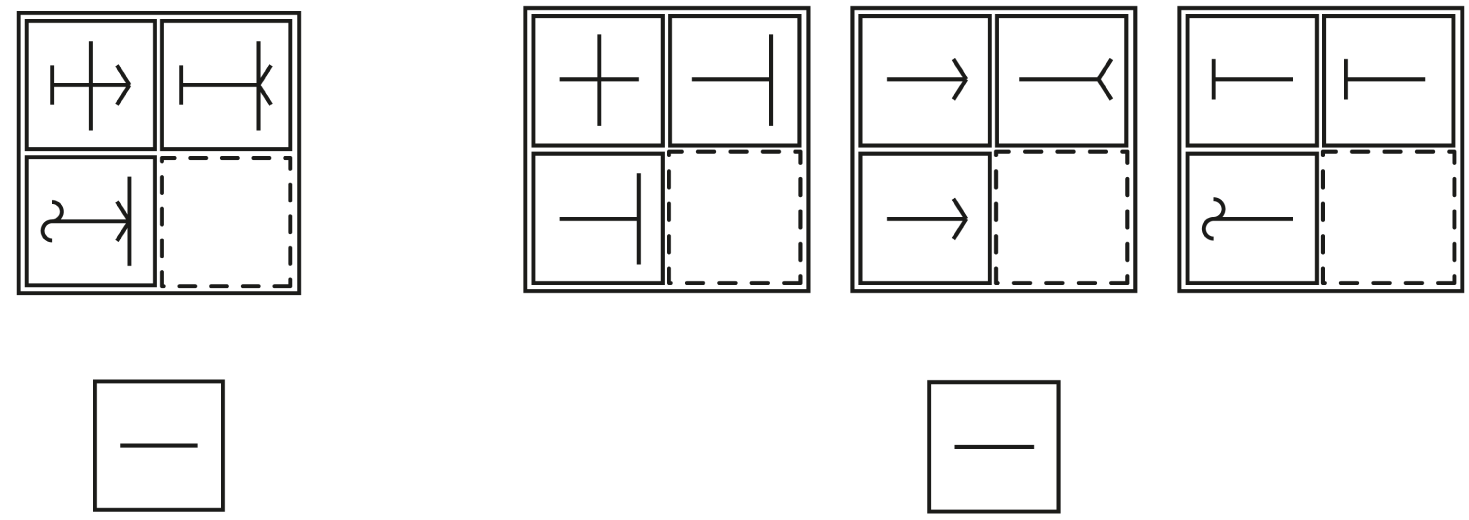

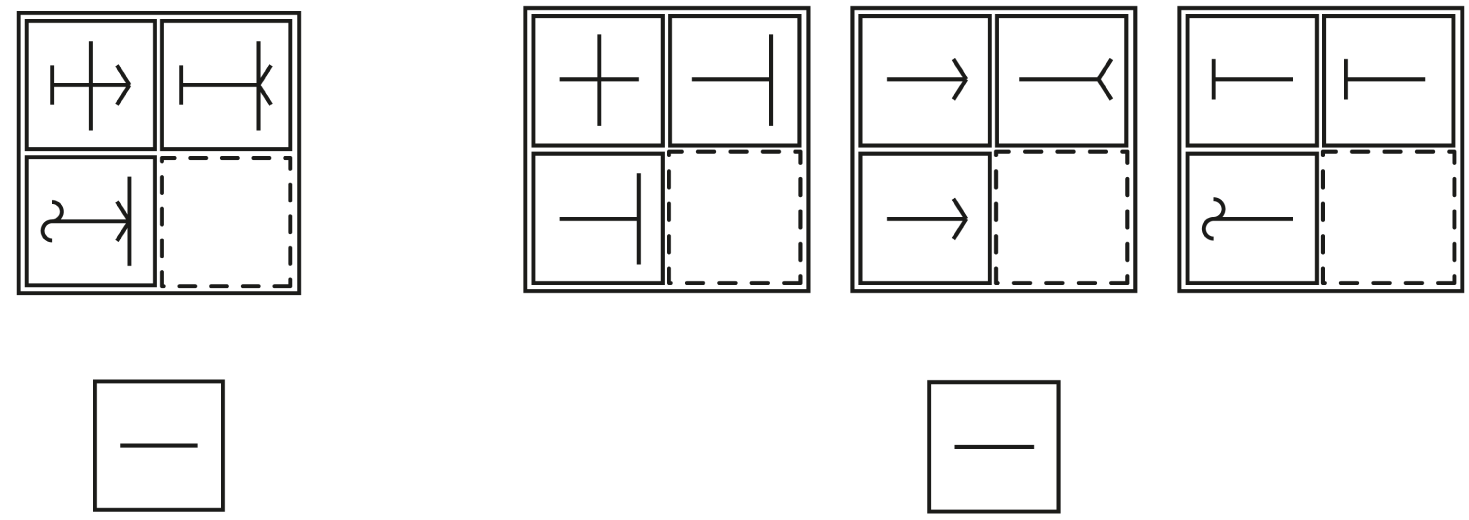

Tests of simple problem solving are important because they predict success in many real life activities, including education and work. Often they are called tests of fluid intelligence. Fluid intelligence is important in meeting many kinds of cognitive challenge, such as dealing with brain diseases, mental health conditions, or developmental or economic disadvantages. Evidently a problem-solving test measures something important, but what is it? We reasoned that, in all goal-directed behaviour, a complex problem must be split into a series of simpler, more focused parts. If this fails, thought and behaviour lack a clear organization and structure. To show the importance of mental segmentation, we presented standard tests of problem-solving already split into their parts. We found that, when problems are split in advance, they become trivially easy. The research confirms that, in standard tests of fluid intelligence, we are measuring the mind’s ability to organize a problem into separate, easily solved parts. This ability is a core mental resource in dealing with many kinds of life challenge.

Duncan, J., Chylinski, D., Mitchell, D. J., & Bhandari, A. (2017). Complexity and compositionality in fluid intelligence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 114, 5295-5299.

After a traumatic event, people often experience intrusive thoughts about the experience. Such memories can be powerfully distressing, so survivors of trauma typically report that they try to suppress them. Fortunately, intrusive thoughts tend to decline over time. But up to now, researchers have not known how this happens: is it merely that memories of a trauma naturally fade as time passes? Or can trying to suppress these memories serve as a kind of training ground for control over one’s thoughts, improving memory suppression through practice? Michael Anderson’s group at the CBU set out to find out. Using a psychological experiment called a Think-No-Think task, which involves trying to selectively forget certain words, they assessed their participants’ abilities to suppress information with different emotional valences. Across two experiments, the team found that participants with a greater history of trauma were better able to intentionally forget neutral and negative words, and exhibited greater forgetting overall. So while intrusive memories are a challenging symptom that many survivors of trauma face, it seems that fighting these memories can give people an opportunity to gain better control over their thoughts. These findings cast light on potential strategies to foster resilience after trauma.

Hulbert JC, Anderson MC. What doesn't kill you makes you stronger: Psychological trauma and its relationship to enhanced memory control. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2018 Dec;147(12):1931-1949. doi: 10.1037/xge0000461. Epub 2018 Jul 19. PMID: 30024184; PMCID: PMC6277128.

An acquired brain injury (ABI) refers to damage to the brain as the result of an interruption to its blood supply (stroke), from a severe blow to the head (traumatic brain injury) or from a brain tumour. Many people make excellent recoveries from these injuries. However, for some, it can bring about major changes that can affect movement, perception, language, memory and many other abilities. ABI is also linked with a hugely increased risk of mood disorder, such as depression. This affects up to 50% of people over the 1-5 years following their brain injury. Perhaps not surprisingly, the more severe the injury, i.e. the more effects it has had on life, work etc., the greater the risk of low mood. However, we also know that two people who have very similar brain injuries and resulting challenges may have very different emotional responses. What makes the difference in this individual response to adversity? If we can identify things that protect mood for some people, can this be used to reduce the risk of depression in others?

Many research studies over the years, including here at the CBU, have examined psychological ‘risk factors’ for low mood in the general population. These, in turn, have led to improvements in psychological therapies to reduce mood problems and the risk of ‘relapse’ in those who have recovered. Much less of this sort of work has been done with people with acquired brain injuries.

CBU scientist Fionnuala Murphy and colleagues examined one potential risk factor for low mood following ABI, the ability to imagine positive things in one’s future. Why might this be important? Well, put simply, if you find it hard to imagine positive things that will happen to you, you might not be motivated to do those activities. If I can’t imagine myself enjoying seeing a film with friends, why would I go through all the effort of checking the film times, catching the right bus and so on? The results of the study showed that people with ABI who had this difficulty also tended to have lower mood, despite their injuries being as serious as others with normal mood. Of course, difficulties in imagining positive events is likely to be just one of many psychological risk factors. Studies like this are useful in identifying potential targets for treatment, for example, in deliberately practising positive future imagination or in using other strategies to maintain positive experiences.

Murphy, F. C., Peers, P. V., Blackwell, S. E., Holmes, E. A., & Manly, T. (2019). Anticipated and imagined futures: Prospective cognition and depressed mood following brain injury. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(1), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12202

Denis Chan and colleagues at the University of Cambridge studied 205 retired individuals from the CamCAN cohort and found that mid-life intellectual, physical and social activities made significant positive contributions to their current cognitive abilities (IQ). The positive effects of mid-life activities also appear to have a protective effect in the face of poor structural brain health. More information about CamCAN can be found on the CamCAN website found here.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was originally conceived as a condition that affected adults, having it’s original origins as a syndrome experienced by war veterans. Over the years, we have increasingly understood that children can experience PTSD also, and the diagnostic criteria (i.e., symptoms that an individual needs to display to receive a diagnosis of PTSD) have been changed to include a subtype of PTSD especially for young children. In this study, we explored whether using the young children PTSD diagnosis increased our ability to identify children who needed help, using large ‘population level’ datasets collected from national surveys. We had a particular focus on children aged 5-6years olds as these were the children the young children PTSD subtype was designed for. We examined data from both the general population and also children in care (i.e., ‘looked after children’). When we used the adult criteria, not a single 5-6 year old in the general population was diagnosed with PTSD, but using the young children PTSD subtype, 5.4% of children who had been exposed to trauma had developed PTSD. In children in care, only 2.7% of trauma-exposed children met the adult criteria, but 57% met the young children PTSD subtype criteria. The young children criteria also appeared to improve identification of older children too. These results show that using the young children PTSD subtype will dramatically improve identification of 5-6 year old children who need help following a trauma.

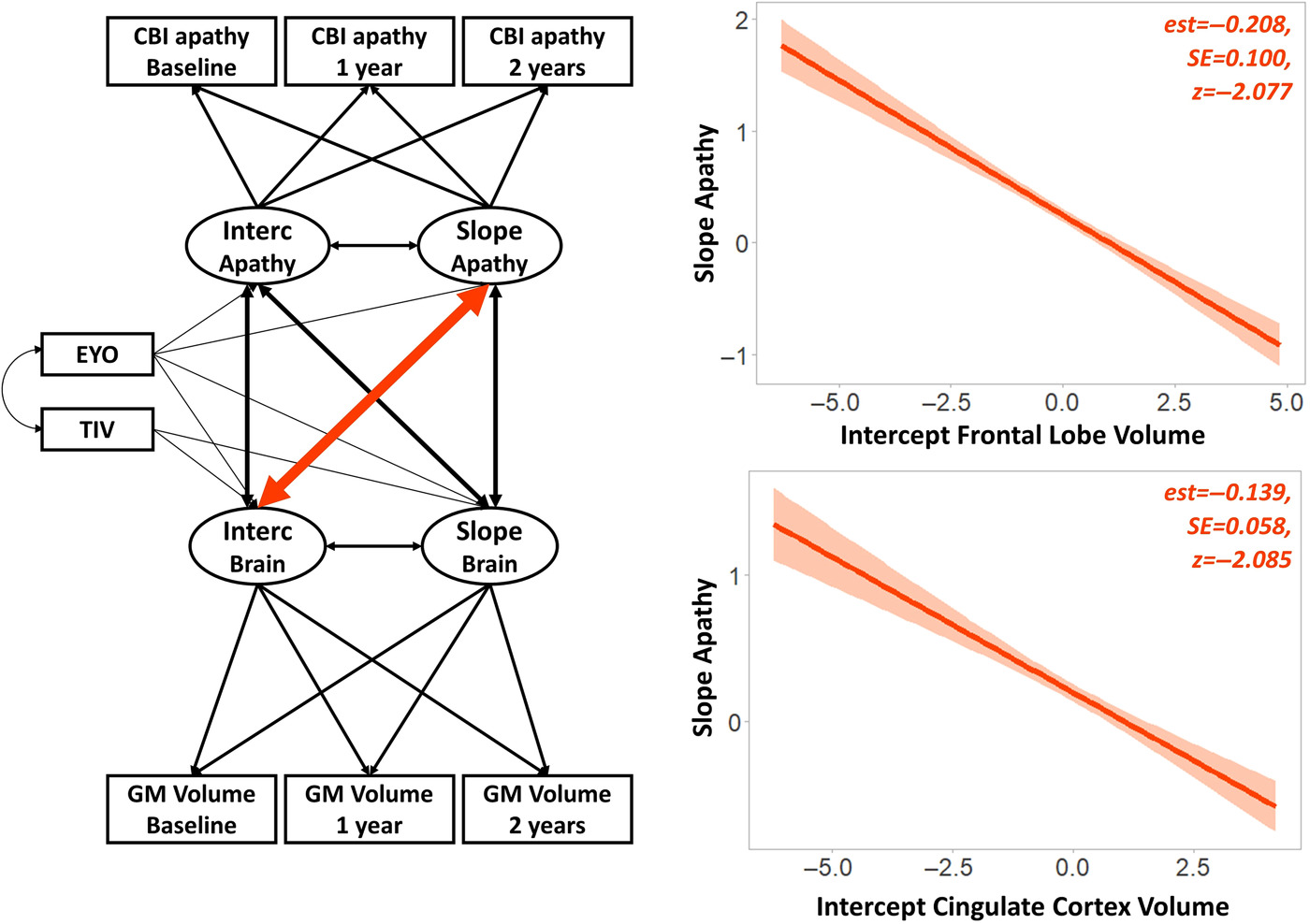

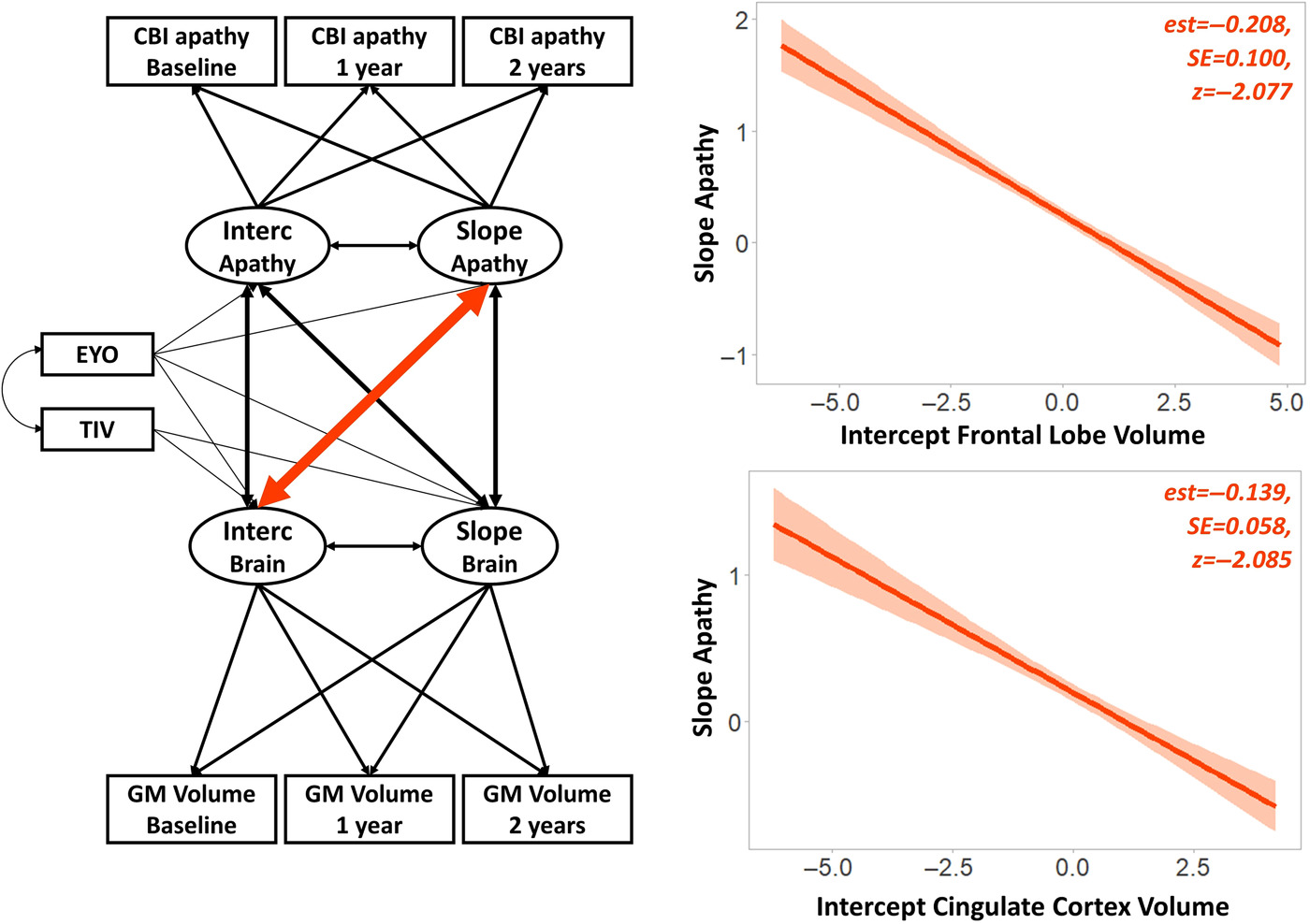

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects regions of the brain involved in key cognitive functions, such as abstract reasoning and emotion regulation. Apathy—a multifaceted construct that describes a range of behavioural and cognitive impairments—has been associated with worse outcomes in FTD. In this study, researchers aimed to understand whether apathy begins to develop before FTD becomes detectable. To do this, they looked at patterns of brain structure, cognition, and behaviour in participants who carried genetic precursors of FTD, but who had not yet developed symptoms of this disease. Over the course of two years, the apathy of asymptomatic FTD carriers became more severe. Baseline apathy was also found to predict cognitive, behavioural, and neurological decline over time. Malpetti and colleagues concluded that apathy is an early marker of FTD-related changes in both brain and behaviour, and that it can predict the speed of deterioration before dementia onset. Importantly, apathy may be a modifiable factor in those who carry the genetic precursors of FTD. Future research and clinical interventions should endeavour to target the causes of apathy in order to prevent the neurological and cognitive problems associated with FTD.

Citation: Malpetti, M., Jones, P.S., Tsvetanov, K.A., Rittman, T., van Swieten, J.C., Borroni, B., Sanchez-Valle, R., Moreno, F., Laforce, R., Graff, C., Synofzik, M., Galimberti, D., Masellis, M., Tartaglia, M.C., Finger, E., Vandenberghe, R., de Mendonça, A., Tagliavini, F., Santana, I., Ducharme, S., Butler, C.R, Gerhard, A., Levin, J., Danek, A., Otto, M., Frisoni, G.B., Ghidoni, R., Sorbi, S., Heller, C., Todd, E.G., Bocchetta, M., Cash, D.M., Convery, R.S., Peakman, G., Moore, K.M., Rohrer, J.D., Kievit, R.A., Rowe, J.B., & Genfi, O. (2020). Apathy in presymptomatic genetic frontotemporal dementia predicts cognitive decline and is driven by structural brain changes. Online ahead of print.

doi: 10.1002/alz.1225.

PMID: 33316852

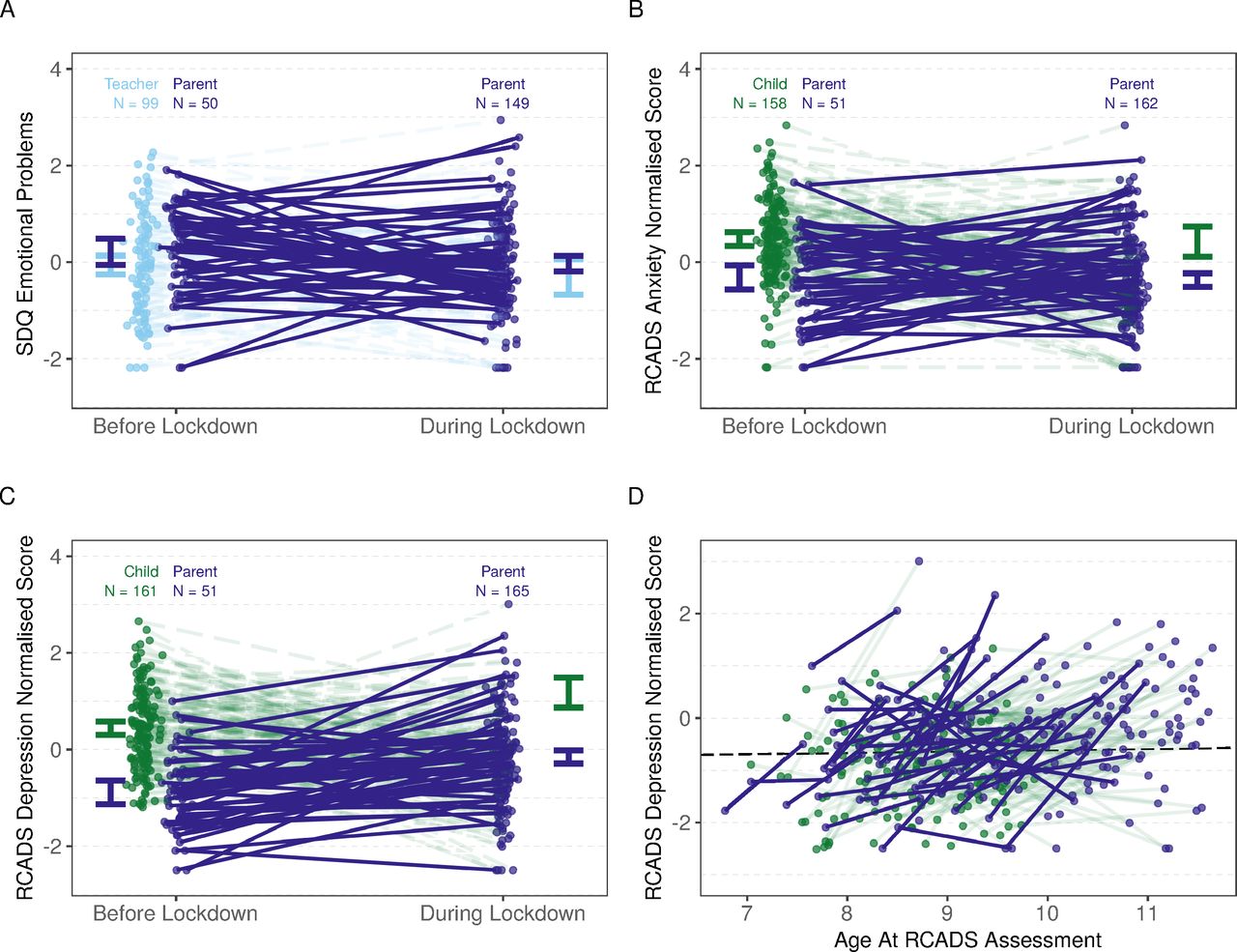

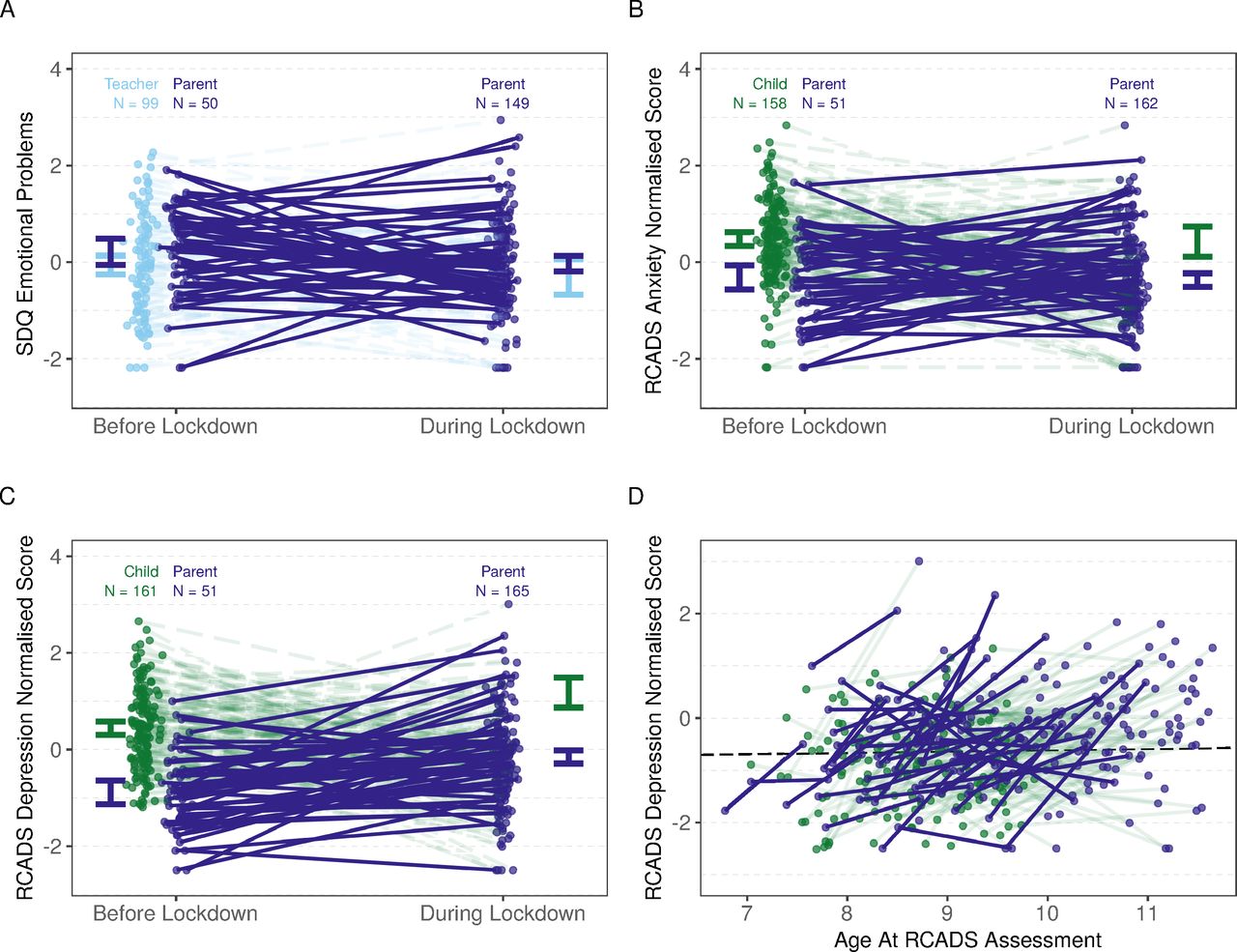

As the first cases of COVID-19 reached the shores of the United Kingdom, the government imposed a national lockdown to protect public health. After schools closed, young people suddenly faced a radically restricted lifestyle, one usually poor in social experiences like interactions with peers. Given the importance of such experiences during development, there was widespread concern about how lockdown might have affected children. This study was one of the first to search for direct evidence that the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown negatively affected child mental health. Using assessments completed by caregivers and teachers, the team re-evaluated the mental and emotional wellbeing of a group of children that they had been following since before the pandemic. The team found that children tended to show worse mental health after the beginning of lockdown. While trajectories were varied, with some children experiencing better mood than before, there was an overall increase in depressive symptoms with a medium-to-large effect size. In light of these results, the UK will likely need to allocate more resources for child and adolescent mental health as it emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic

Citation: Bignardi G, Dalmaijer ES, Anwyl-Irvine AL, et al. Longitudinal increases in childhood depression symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown. Archives of Disease in Childhood Published Online First: 09 December 2020. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2020-320372

MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit

MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit