Cohorts

The MRC CBU provides world-leading research facilities and technical support that form the essential infrastructure for our science. A core part of this is developing and applying novel methods for understanding cognition and the brain, in health and disorder. Multiple programmes work together to share methods expertise and new tools, and where possible we make these available across the international neuroscience community.

We have created and now host multiple specialist cohorts of participants, recruited across the lifespan, and based on diverse criteria including mental health difficulties, socio-economic disadvantage, brain injury, neurodevelopmental risk, genomic disorder, deafness, age and neurodegenerative diagnosis. These are a vital shared resource across our research programmes.

Find out about CBU Cohorts

Brain and Behaviour in Intellectual Disability of Genetic Origin (or BINGO for short) is a long-running research project to understand more about learning and mental health in young people affected by rare genetic disorders. Within BINGO, we focus on specific genetic diagnoses which affect how brain cells work, for example how signals are sent from one brain cell to another. We want to know whether people who share similar genetic differences experience similar problems (for example, difficulties with movement, vision or communication) because of the effect that their genetic differences have on brain development.

To find out more about BINGO, including information about taking part, please visit: https://www.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/bingo/

In our Resilience in Education and Development (RED) project, we want to establish which factors help children flourish despite socio-economic disadvantage. We visit schools with our own iPad app, which assesses children’s cognition through multiple games, and incorporates multiple age-appropriate questionnaire. This app provides us with a detailed assessment of different cognitive skills, literacy, numeracy, mental health, home life, school life, and a whole series of demographic details. A subset of the cohort also visit the Unit for brain scans. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetoencephalography (MEG), using a series of tasks, we are able to explore both structural and dynamic brain mechanisms. The study is longitudinal, by revisiting the schools and reinviting children to the Unit, we track changes over time. Ultimately, we hope to learn more about the development of cognition and brain organisation, and how specific circumstances like socioeconomic status help shape child development.

Why do certain children struggle to learn? Traditionally, researchers have sought to answer this question by looking at specific groups of children, such as children with ADHD or dyslexia, for example. But the Centre for Attention, Learning, and Memory (CALM) is taking a different approach, building a large cohort of children who were referred by specialists for having any problem with attention, learning, or memory. The CALM cohort now includes 800 children between the ages of 5-18. Some have a few different diagnoses – and some have no diagnosis at all. CALM is following these children as they grow up, and collecting data on their cognitive abilities, brain structure and function, and genetics. By analysing this rich longitudinal data, researchers at CALM have identified unique cognitive and neural profiles of children who have difficulties in attending, listening, and remembering. With the help of CALM, we are closer than ever to understanding how and why children struggle in school.

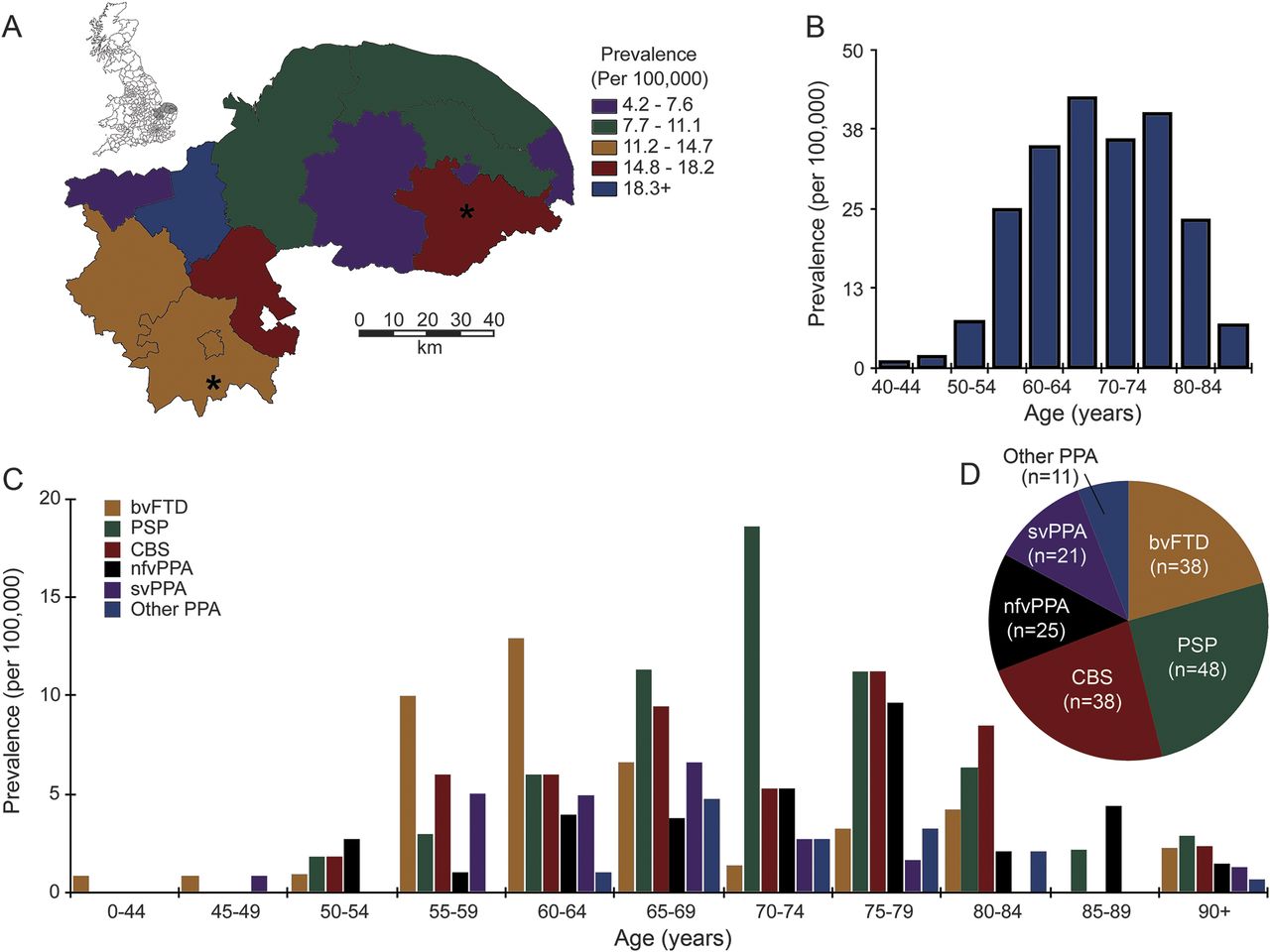

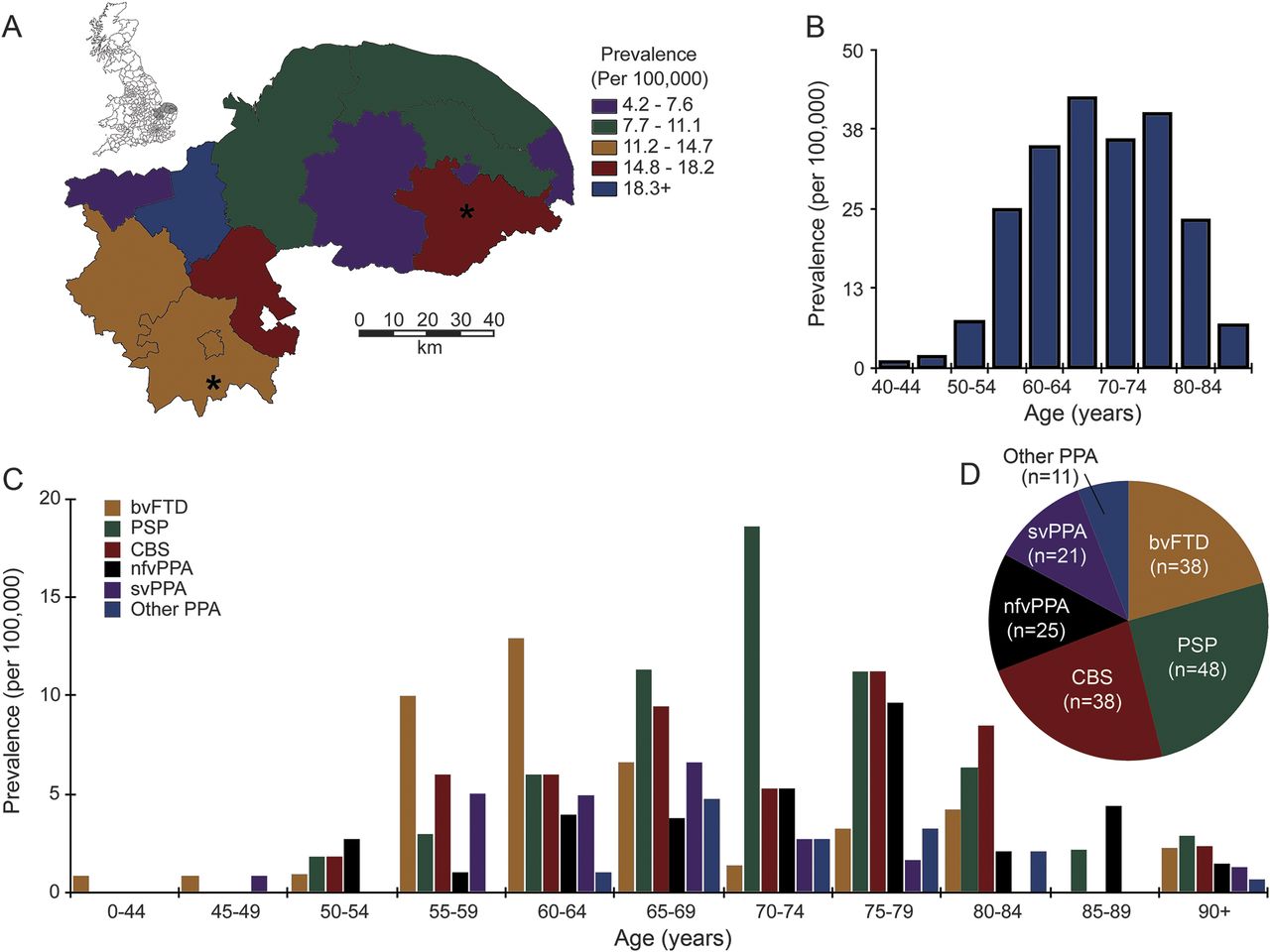

Many of our most foundational human abilities rely, in some way, on neurons located in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. It comes as no surprise, then, that frontotemporal damage – through a stroke, for instance, or a neurodegenerative disease – can result in a wide range of symptoms, from difficulties with speech to apathy and impulsivity. But clinicians are still far from understanding the prevalence of such “frontotemporal lobar degeneration” syndromes, let alone their typical characteristics and how they change over time. The goal of the PiPPIN study (Picks disease and progressive Supranuclear Palsy Prevalence and Incidence Study) is to change this. Since 2013, PiPPIN researchers have been studying the brains and cognitive abilities of individuals affected by frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Their exciting findings are enabling healthcare professionals and loved ones alike to better care for these patients.

Over the course of our lifetimes, each of us has unique experiences: we may receive a certain education, develop unique abilities, and suffer particular diseases or setbacks. How does the brain change in dialogue with experience over the lifespan, and which factors contribute to its health and flourishing? In order to answer this question, the Lifebrain project has brought together data from 18,500 research participants collected in 11 European brain-imaging studies – including our very own CamCAN and CALM studies. Through the collaborative efforts of outstanding researchers, findings from the Lifebrain project are beginning to sketch a complete picture of brain development, mental health, and cognition across the entirety of a human lifetime.

Brain structure changes dramatically as we get older. But changes in cognition are more varied: most of us experience rapid decline of abilities, such as memory, and almost no decline at all in others, such as language comprehension. How does the brain reorganise later in life, and why are these structural changes linked to the typical impairments of old age? These questions gave rise to the CamCAN study, a longitudinal study of 700 individuals from the ages of 18 to 88. Using measures of cognition, brain structure and brain function, CamCAN researchers are untangling the complex changes taking place in the aging brain. Based on these findings, they are investigating when (and how) it’s best to intervene to help people maintain their cognitive abilities as they get older.

Link: https://www.cam-can.org

MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit

MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit