Understanding Complex Disorders

Psychological and cognitive disorders are complex and difficult to treat. Often the underlying mechanisms are unknown and the response to intervention is highly variable. A critical barrier to making progress arises from the ill-fitting diagnostic systems used to categorise these disorders. People with the same diagnosis are often very different from one another, and very often, the same person has symptoms crossing several traditional diagnoses. We address this challenge by taking a ‘transdiagnostic’ approach across a wide range of cognitive and psychological disorders.

This transdiagnostic approach looks beyond traditional diagnostic categories and instead embraces the complexity of psychological and cognitive conditions. We believe that focussing on signs, symptoms and processes that cut across traditional diagnostic boundaries will provide a better link to underlying mechanisms, and improved pathways to individualised prevention and intervention.

Research programmes across the MRC CBU are working to deliver this much-needed shift in approach across neurodevelopmental disorders, mental health, dementias and brain injury.

Our Transdiagnostic Research

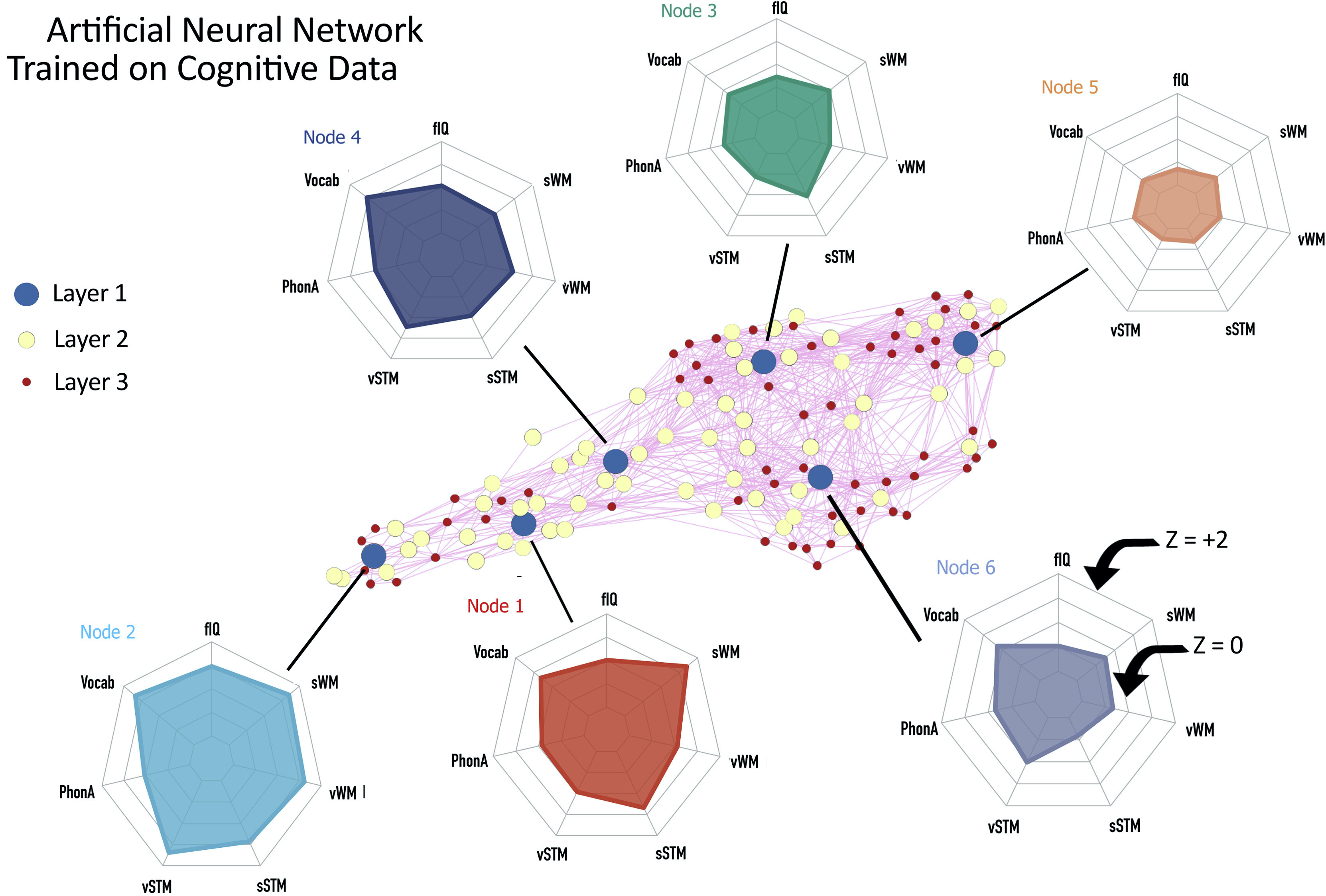

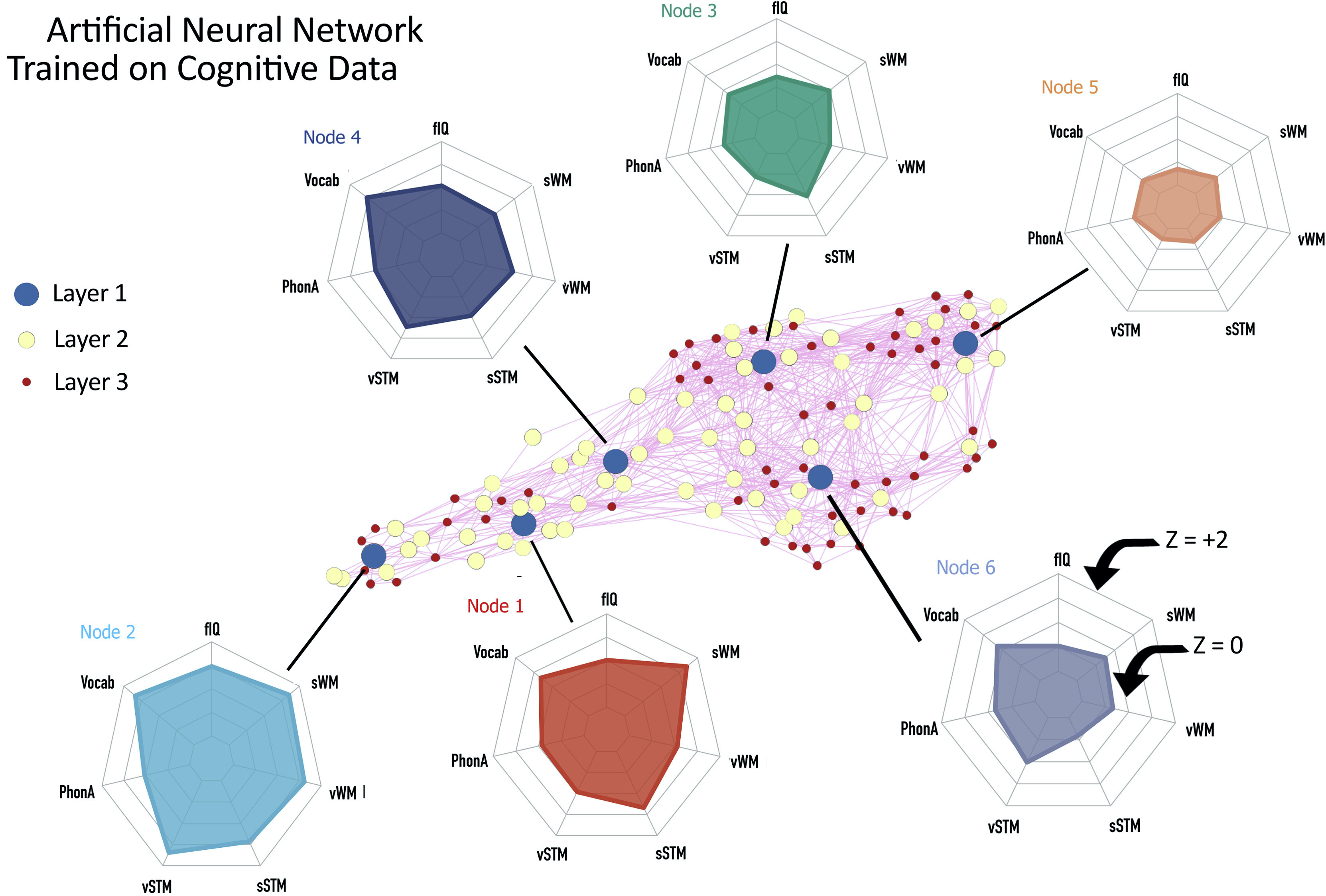

When kids struggle in school, one of the first steps toward getting them help is often labelling their difficulties with a formal diagnosis, like attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, or dyslexia. But few children experience symptoms that fit neatly a single category – a complication that has hindered efforts to uncover the origin and mechanism of learning difficulties. This study took a different approach. Using machine learning, the research team identified groups of children who shared similar cognitive profiles, or patterns of performance on tests of attention, learning, and memory. With data from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the team discovered associations between cortical structure and a range of cognitive profiles across children, rather than specific links between brain regions and particular cognitive difficulties. Then, the team evaluated the organisation of the children’s brain networks using diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). They found that children with more widespread and severe difficulties had poorly connected hubs, regions that play an important role in efficient communication across the brain.

Citation: Siugzdaite, R., Bathelt, J., Holmes, J., and Astle, D. E. (2020). Transdiagnostic Brain Mapping in Developmental Disorders. Curr. Biol. 30, 1245-1257.e4.

doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.01.078.

Around 1% of the global population has intellectual disability (ID, also known as learning disability), meaning lifelong difficulties with cognitive functions. With recent advances in genomic technologies, it is possible to find a specific cause (genetic diagnosis) for the majority of people with severe ID. But whether and how genetic diagnosis is relevant to each person’s social and emotional characteristics remains uncertain.

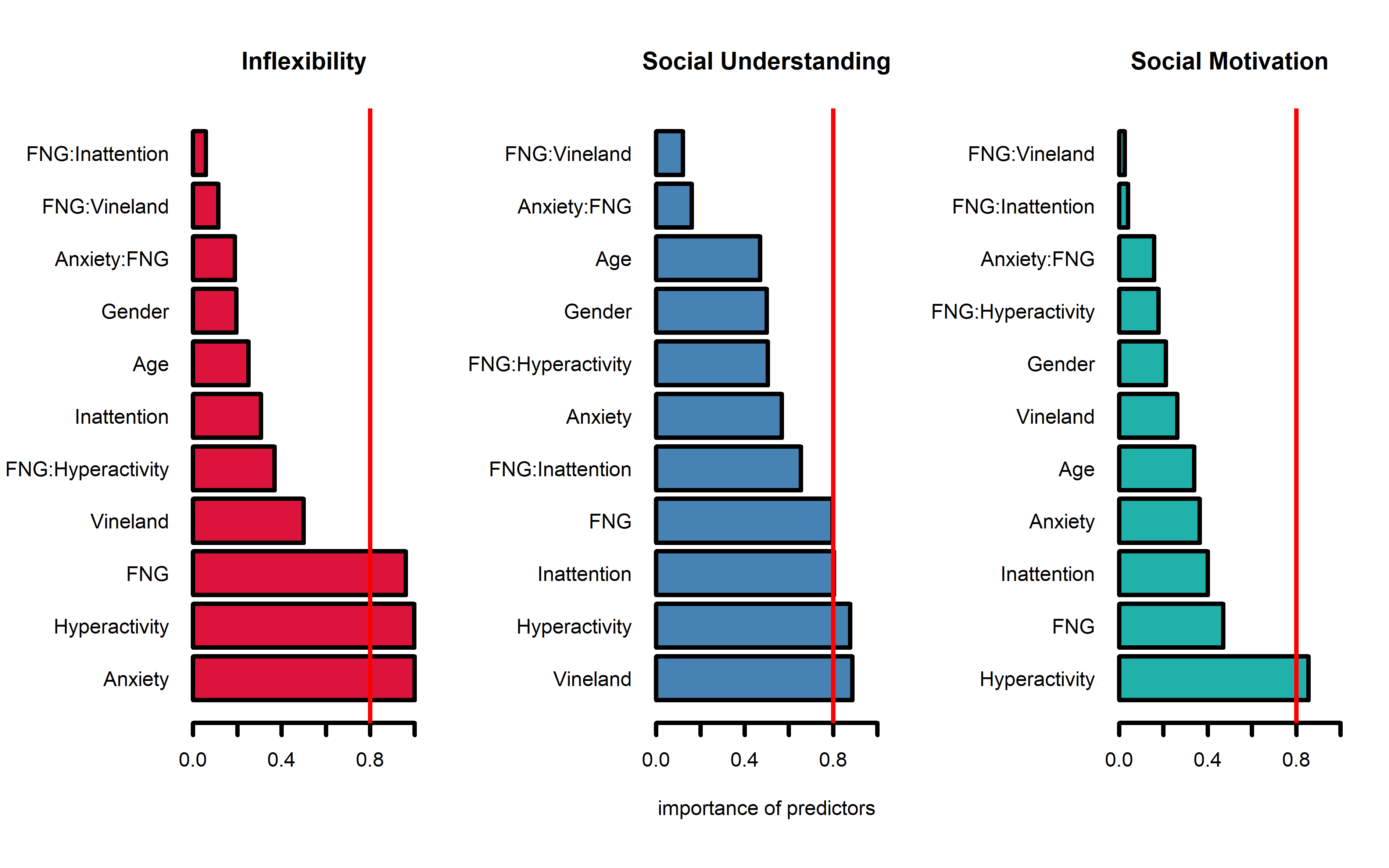

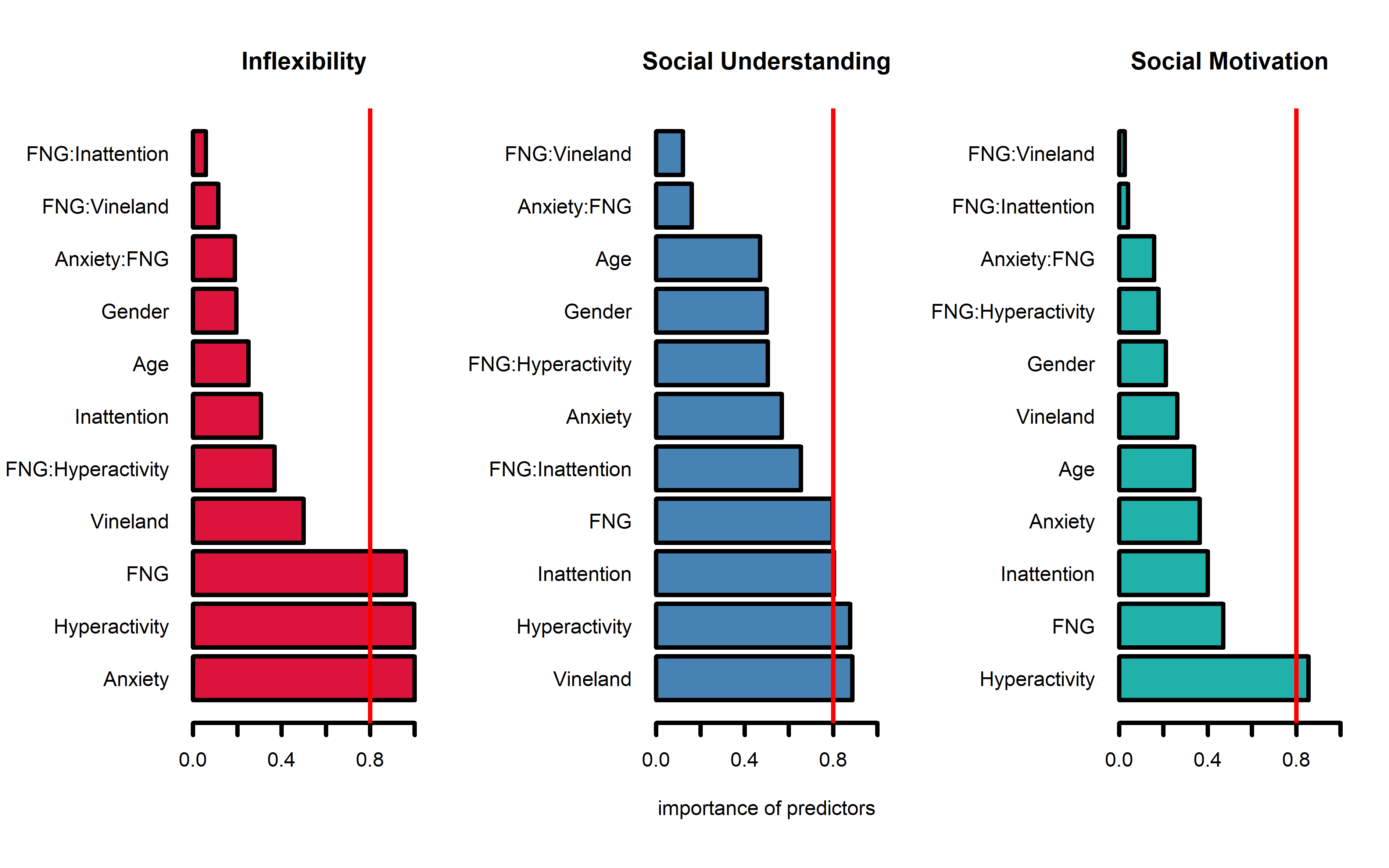

This study asked whether genetic diagnoses influence aspects of the autism spectrum amongst young people with ID. We explored three dimensions which contribute to autism: flexibility, social understanding, and social motivation. We found that the overall likelihood of autistic characteristics was unaffected by genetic diagnosis. Social understanding and social motivation were not strongly linked to genetic diagnosis, even when other background factors were taken into account. These results emphasise the complexity of influences on each person’s social and emotional development, with specific genetic diagnosis having limited influence in the context of many other factors.

However, we did find that young people with genetic diagnoses affecting DNA transcription (chromatinopathies) are more likely to show inflexible behaviours when compared to young people with other genetic diagnoses. Looking more closely, we found that inflexibility and hyperactivity often occur together in people with chromatinopathy diagnoses, suggesting a specific developmental pathway toward these co-occurring features. In future studies we will explore aspects of this pathway, which may lead to new ways of understanding and supporting individuals with ID due to chromatinopathy gene variants.

Brkić D, Ng-Cordell E, O'Brien S, Scerif G, Astle D, Baker K. Gene functional networks and autism spectrum characteristics in young people with intellectual disability: a dimensional phenotyping study. Mol Autism. 2020 Dec 11;11(1):98.

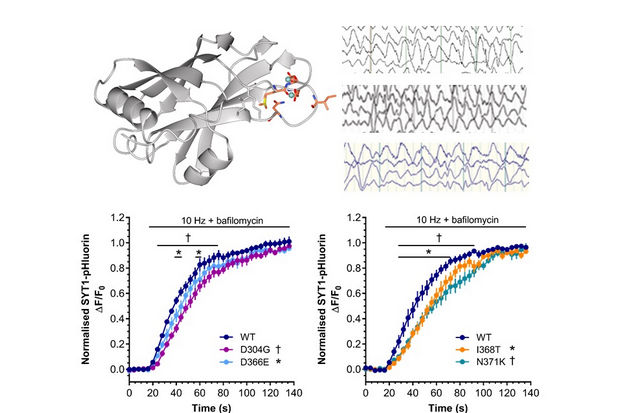

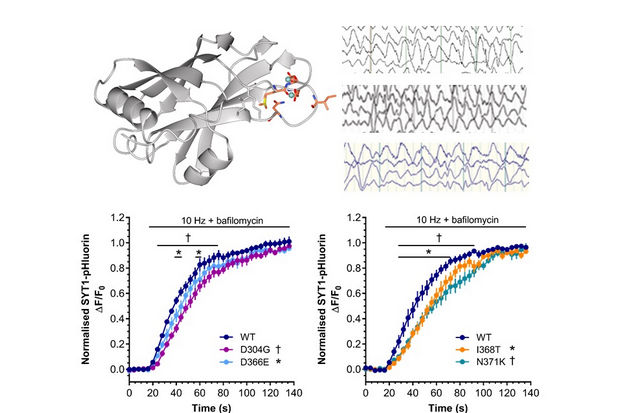

In 2015, Kate Baker and colleagues published the first report of a child with severe, complex disabilities and a variant in a gene called Synaptotagmin 1 (SYT1). SYT1 co-ordinates communication between brain cells by triggering the release of neurotransmitter-filled vesicles. Following this discovery, genomic testing laboratories around the world began to look for similar cases. By 2017, ten more cases of SYT1 variant had been identified worldwide. Most of these children do not use speech to communicate, spend a lot of time chewing their fingers, and are described as unpredictable, switching from calm to agitated for no obvious reason. Another striking similarity is an unusual pattern of brain electrical activity, not seen in other neurodevelopmental disorders.

To understand how SYT1 variants affect brain function to cause this spectrum of problems, Kate teamed up with Sarah Gordon, a synaptic physiologist at the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health in Australia. Sarah’s team found that the SYT1 variants identified in patients affect brain cells by slowing down vesicle release in response to electrical activity. We now hope to understand how SYT1 variants and neurotransmission speed influence cognitive development, leading to the symptoms experienced by patients. The ultimate goal is to discover safe and effective therapies to improve quality of life for children and adults with SYT1 variants.

Baker K, Gordon SL, Melland H, et al. SYT1-associated neurodevelopmental disorder: a case series. Brain. 2018;141(9):2576-2591. doi:10.1093/brain/awy209

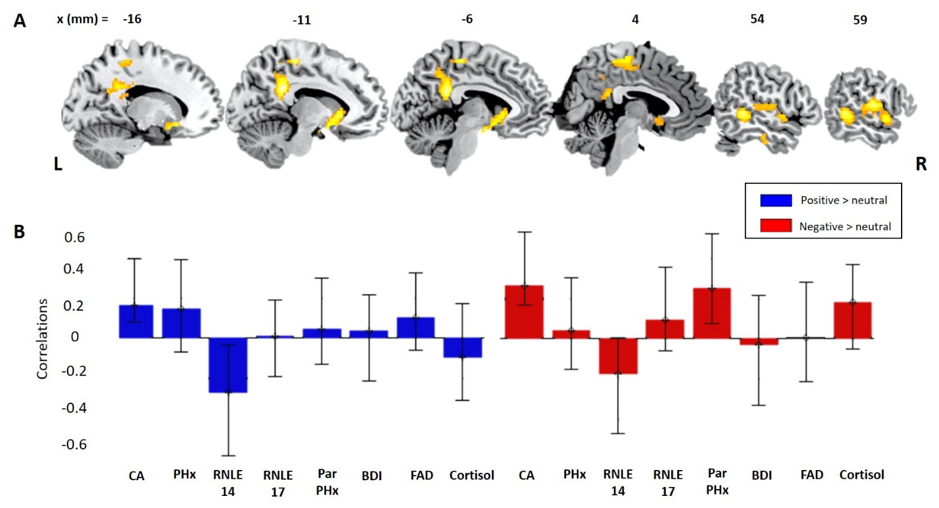

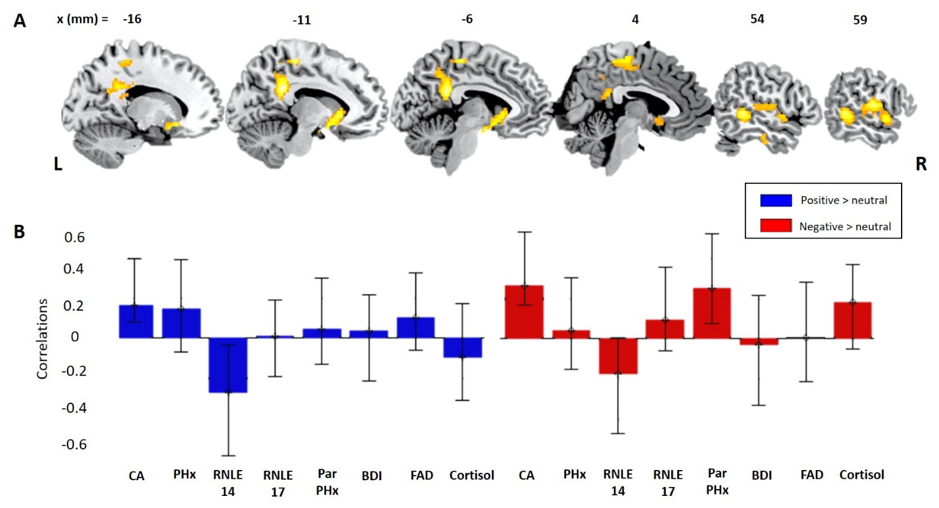

Depression is leading cause of disability worldwide. There are lots of different risk factors for depression; from biological ones such as genetics, to psychosocial ones such as childhood adversity. Depression is often first diagnosed in adolescence, so it is important to try and understand how the combined effects of risk factors interact with everyday emotional responses to social situations such as rejection and inclusion. Here, the team used a population-derived sample of adolescents to explore the relationships between biopsychosocial risks for depression, emotional response style and brain activity to being socially rejected and socially included. Using Partial Least Square regression and correlation models, we identified higher depressive risk was associated with a blunted emotional responses to both rejection and inclusion. This was linked to patterns of brain activity in emotional control regions of the brain. Importantly, these patterns held when we excluded adolescents who had already been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, a high-risk subsample that had effectively navigated adolescence without reporting mental health difficulties. Thus, this study suggests that a blunted emotional response style to everyday social situations, together with increased activity of emotional control regions of the brain, may be a potential marker of resilience in adolescents at risk of depression.

Citation: STRETTON, J., Walsh, N., Mobbs, D., SCHWEIZER, S., van Harmelen, A., Lombardo, M., Goodyer, I. & DALGLEISH.T. (2021). How biopsychosocial psychiatric risk shapes behavioral and neural responses to social evaluation in adolescence. Brain and Behaviour http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/Z2RYJ

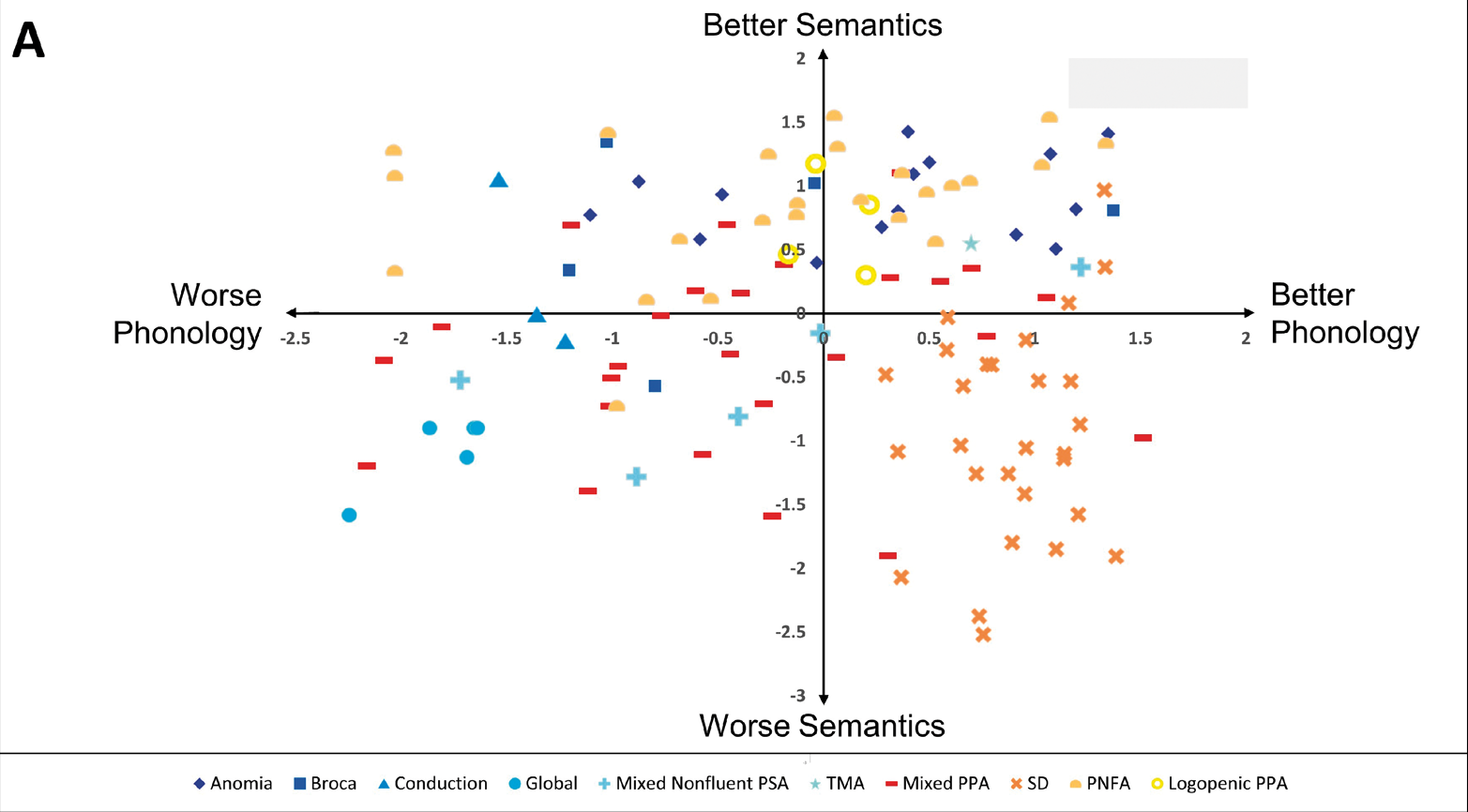

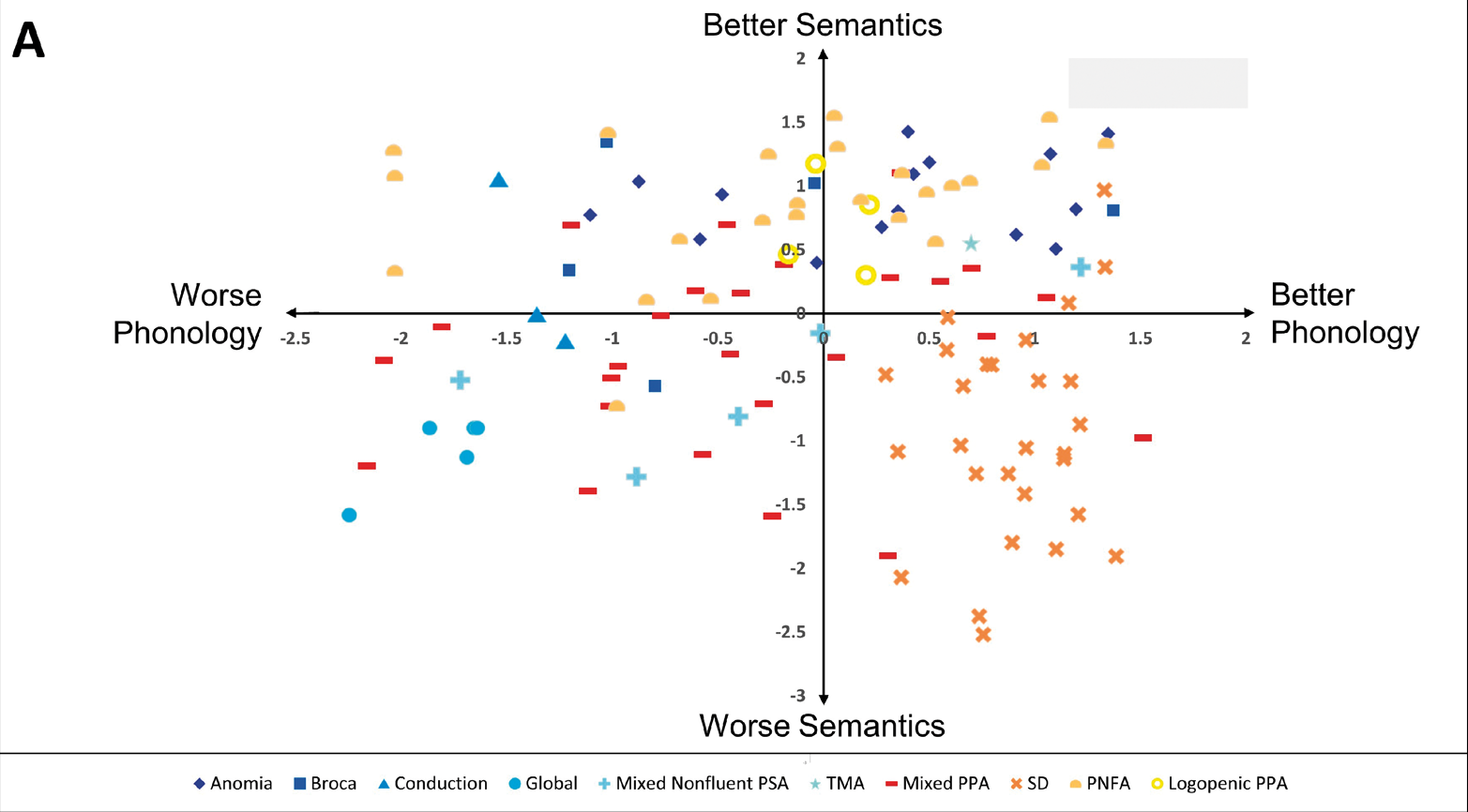

When a patient suffering from brain damage struggles to speak or understand others speaking, she typically receives a diagnosis of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) or post-stroke aphasia (PSA). The label she is given depends on the cause of her brain damage: is it neurodegeneration or stroke? But while the underlying causes of PPA and PSA differ, their symptoms and subtypes usually overlap a great deal. So scientists from the CBU decided to conduct a detailed comparison of the two conditions – something that no study had done before. Using the data-driven method of principle component analysis, the authors discovered that variations in the patients’ language abilities unfolded along four continuous dimensions: phonology, semantics, speech production, and cognition. Then, with a classification analysis, the authors found that categorising patients based on multiple dimensions – rather than a single category – offers a better explanation of both PPA and PSA. Thus, by stepping away from the traditional diagnostic groupings, this research illuminates the path to clinical care for the many patients whose symptoms do not neatly fit into existing diagnoses.

Citation: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32940648/

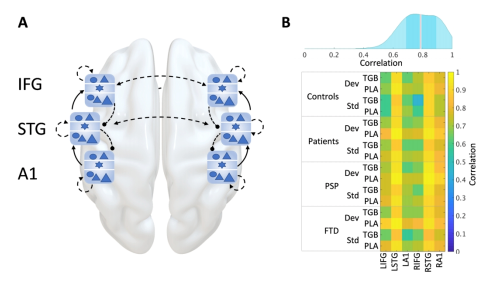

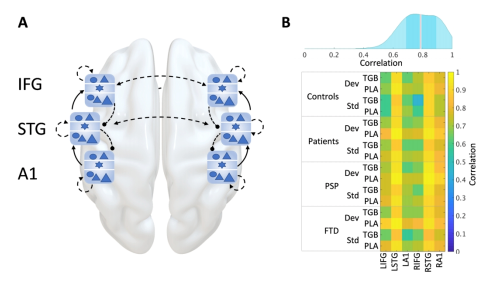

Clinical syndromes caused by frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), including the behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), are pathologically distinct but share many behavioural, cognitive and physiological features. These shared features may in part occur from common deficits of major neurotransmitters like GABA. To further investigate the link between GABA deficits and bvFTD and PSP, 32 patients (17 bvFTD, 15 PSP) and 20 controls undertook a randomised placebo-controlled double-blind pharmaco-magnetoencephalography (MEG) study: two MEG sessions once on placebo and once on 10 mg of tigabine, an oral GABA reuptake inhibitor. Participants also completed neuropsychological tests. Researchers identified deficits in frontotemporal processing via conductance-based biophysical models of local and global neuronal networks. For instance, reduced top-down connectivity from frontal to temporal cortex was related to clinical measures of cognitive and behavioural change while GABA levels were reflective of this connectivity. This study highlights the potential of dynamic causal modeling to clarify mechanisms of human neurodegenerative disease. Utilising model-based physiology and targeted pharmacology (i.e., targeting neurotransmitter deficits) may be particularly effective for FTLD syndromes.

Adams, N. E., Hughes, L. E., Rouse, M. A., Phillips, H. N., Shaw, A. D., Murley, A. G., Cope, T. E., Bevan-Jones, W. R., Passamonti, L., Street, D., Holland, N., Nesbitt, D., Friston, K., & Rowe, J. B. (2021). GABAergic cortical network physiology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. BRAIN. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awab097

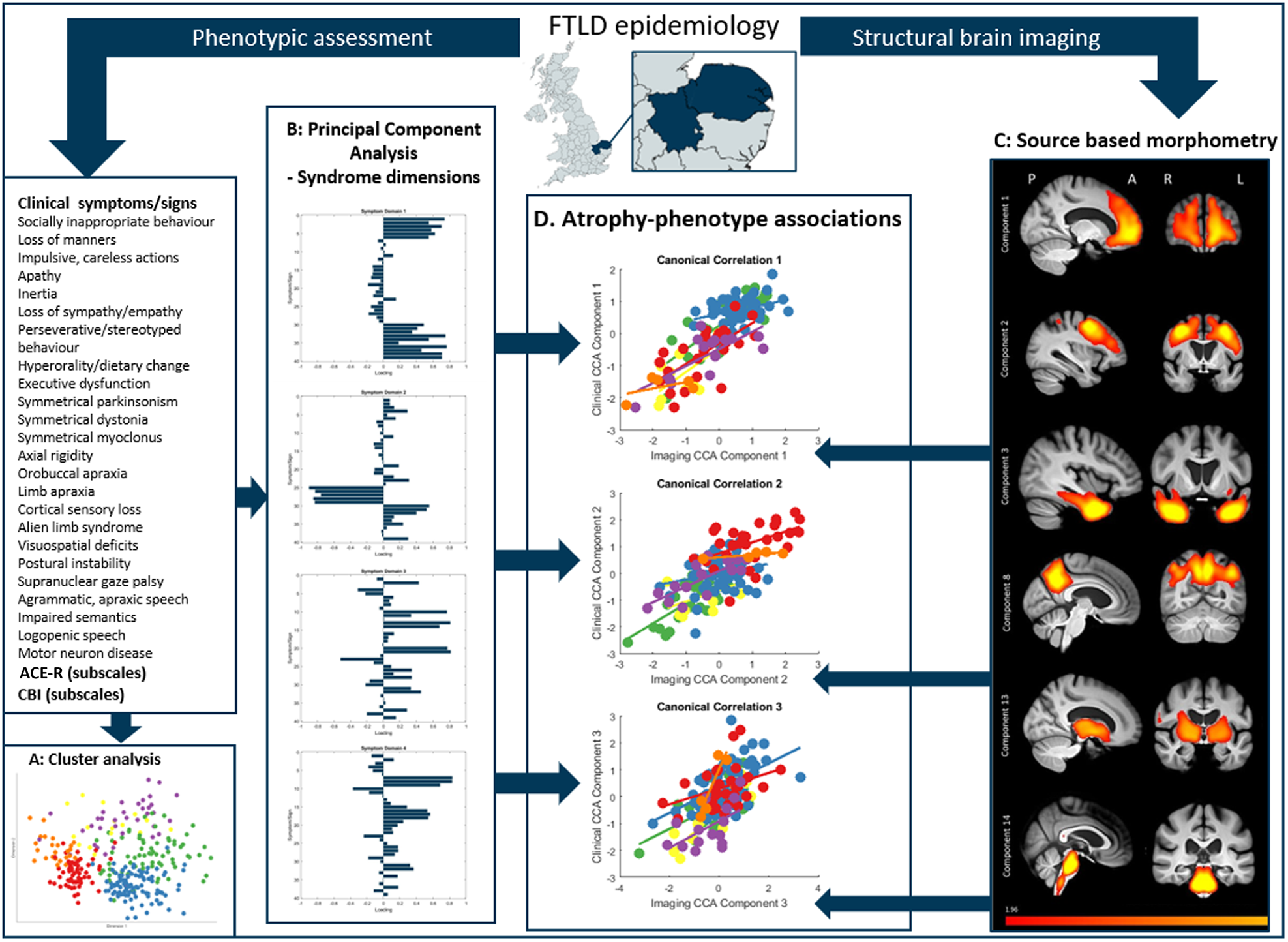

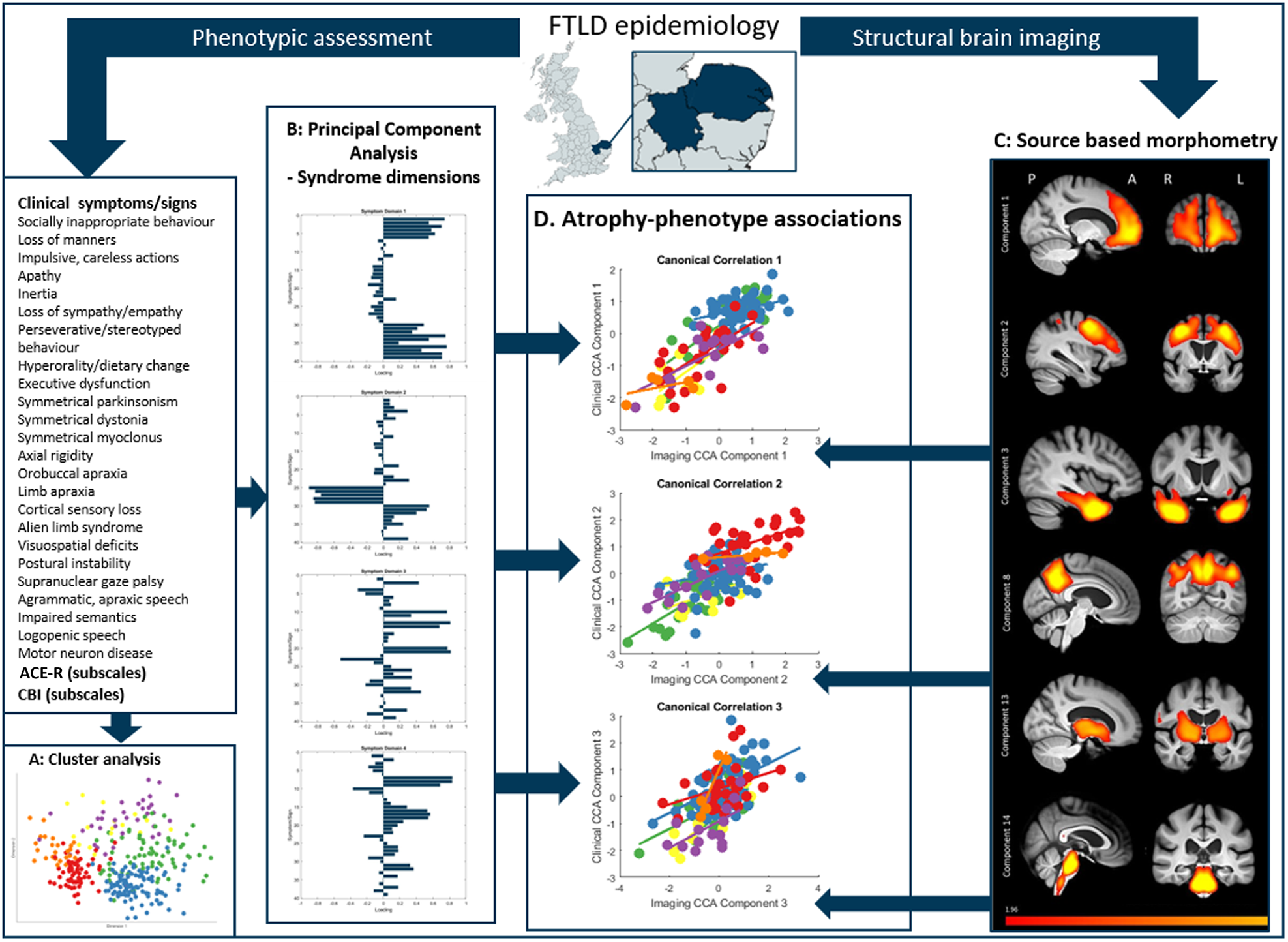

Degeneration in the frontal lobes of the brain can produce many different syndromes, which have highly variable and overlapping clinical features. While clinical diagnostic criteria for these conditions has been refined in the last decade, a transdiagnostic approach to frontal lobe degeneration—which looks at variations in cognitive and behavioural traits, rather than diagnostic labels—may prove to be better in explaining how changes in brain structure drive patient outcomes. In this study, researchers examined 310 patients with cognitive symptoms likely caused by frontotemporal degeneration. Across all the diagnostic groups represented in the sample, behavioural disturbances were present. In order to understand the relationship between the brain and behaviour, Murley and colleagues used a canonical correlation analysis to look at how patterns of brain atrophy related to each other across their sample. They found three distinct brain-behaviour relationships, which varied in continuously across the cohort and drove symptom severity. This indicates that the syndromes associated with frontotemporal degeneration are not represented well by discrete diagnostic categories, but rather, that they exist in a multidimensional spectrum. In other words, patients often experience attributes of multiple disorders, and these variations are reflected in structural differences in the brain. It is important to recognize individual differences in clinical phenotype, both for clinical management and to understand pathogenic mechanisms. A transdiagnostic approach to the study of frontotemporal degeneration syndromes provides a useful framework with which to understand disease aetiology, progression, and heterogeneity and to target future treatments to a higher proportion of patients.

Citation: Murley, A.G., Coyle-Gilchrist, I., Rouse, M.A., Jones, P.S., Li, W., Wiggins, J., Lansdall, C., Rodríguez, P.V., Wilcox, A., Tsvetanov, K.A., Patterson, K., Lambon Ralph, M.A., & Rowe, J.B. (2020). Redefining the multidimensional clinical phenotypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration syndromes. Brain, 143(5), 1555-1571.

doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa097.

PMID: 32438414

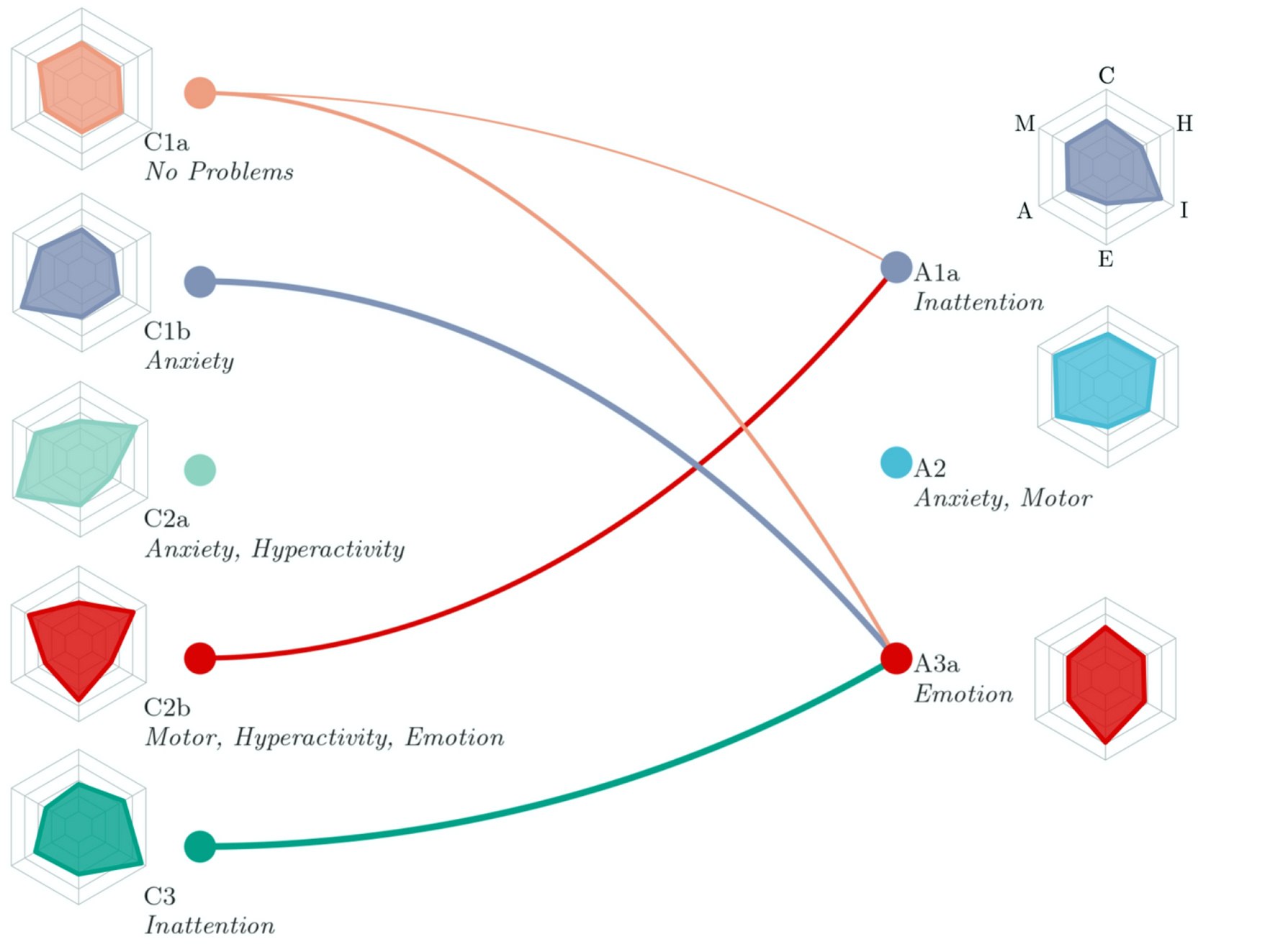

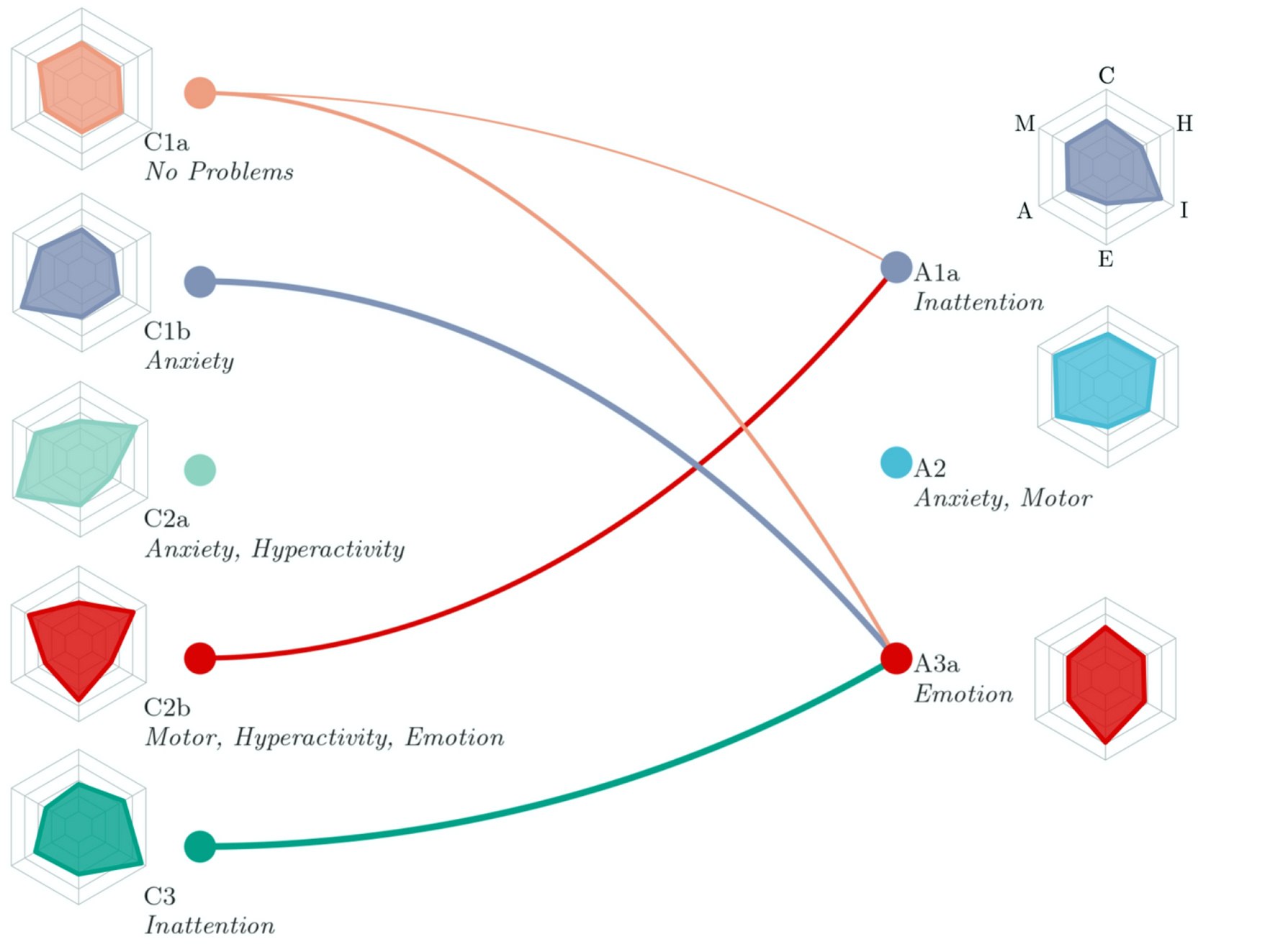

Early intervention is a powerful weapon in the fight against rising rates of mental illness. But in order to intervene before problems become serious, we must accurately predict which children will struggle later in adolescence and what symptoms they are likely to experience. Toward that end, this study followed nearly seven thousand participants from the British Cohort Study as they transitioned from childhood to adolescence. First, the team implemented hybrid hierarchical clustering to identify common patterns of emotional and behavioural problems at both ages. The patterns differed substantially between the two time points, which shows that early problems may appear in new ways as children grow up. Then, the team tested which transitions – or changes in subgroup across development – occurred more often than would be expected at random. A few specific patterns emerged: multiple common problems converged on emotional problems in adolescence, while early motor symptoms later shifted to inattention problems. Fortunately, over half of children also transitioned to having no difficulties in adolescence; these children tended to come from wealthier families and have higher cognitive ability. Thus, efforts to prevent the emergence of mental illness should take into account both the outward presentation and the context of behavioural difficulties in childhood.

Citation: Bathelt, J., Vignoles, A. & Astle, D.E. Just a phase? Mapping the transition of behavioural problems from childhood to adolescence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-02014-4

MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit

MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit