Across history, each new generation has always faced it’s own challenges. These arise out of the cultural and technological context people grow up in. Our Unit was established in 1944, as the Applied Psychology Unit (APU), when the challenges and stresses were defined by the nature of war and the requirements of the military. Today, renamed as the Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit (CBSU) in 1998, the challenges we face as an affluent culture of the C21st are quite different. While technology fulfils pervasive and mostly more constructive, rather than destructive roles, our everyday challenges and stresses lie more in optimising the benefits of education, maintaining physical and mental health across the lifespan while coping with the multitasking demands of family, work and our wider society.

Continuity of Scientific Themes

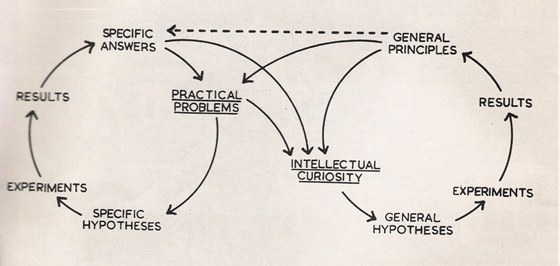

An early depiction by Mackworth (1955) illustrating relationships between applied research and general scientific principles).

While there are huge differences between life in the 1940’s and our lives now, the deeper challenges for research on behavioural, psychological and brain systems are really quite similar. As life calls upon us to behave or think in new or just different ways, science needs to adapt by developing methods that enable it to describe, measure and analyse new phenomena. New phenomena, in their turn, typically expose gaps or weaknesses in our theories and understandings. Improved theoretical understanding and knowledge can then provides a platform from which we can think about how to put our knowledge to good use – by helping to change how things happen in the home, workplace or clinic. As one of the MRC family of Units, applications of the products of our basic science is focussed on well-being and health – both broadly defined. The unit’s cumulative success is reflected in its size. It has grown from fewer than twenty researchers in the war years to considerably more than a hundred now. As one of the largest and most long-lasting contributors to the development of psychological theory and practice in the UK, if anyone were to glance over more than six thousand papers that make up our cumulative output they would no doubt notice that the language, analyses and metaphors that are used in describing behaviour, minds and brains changes substantially over the years. But the deep structure and culture of the institution, as well as the kinds of question we seek to answer all remain constant: we develop methods, establish pertinent phenomena, develop and test new theories and use that knowledge in the service of assessing and promoting human well-being. While much changes in society, the underlying composition and functioning of minds and brains is pretty much the same as it was for our immediate and distant ancestors. So key basic questions recur. How do we remember and attend to things? How do we recognise different objects or faces? How does stress, emotion or multiple demands influence how we go about acquiring new skills or performing specific tasks? What happens when our brains are damaged or age? These are just a few examples of fundamental questions that guide what we have done and continue to do.

In this brief historical overview we will simply highlight the major themes and point interested readers to areas of this website where they can find different perspectives on our history (e.g. A timeline; A conference on Unit History to 2004 with presentations by key researchers past and present; and an electronic archive of documents, photographs and films. We also provide key summarises of how Unit research has had an impact outside the Laboratory.

War Time

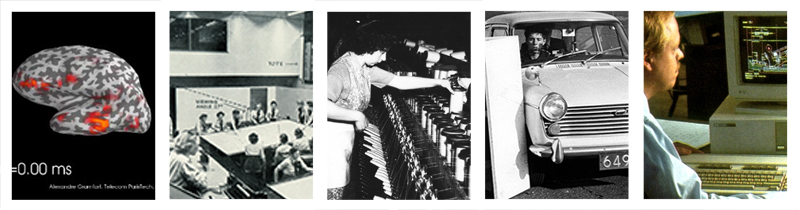

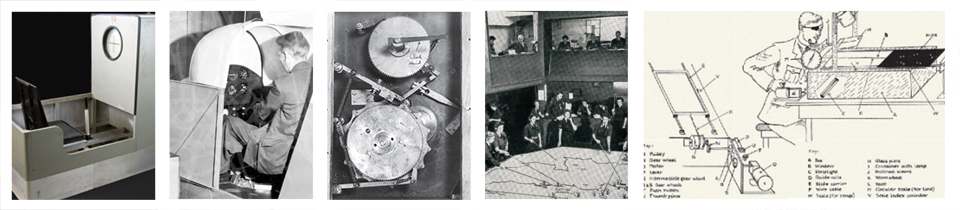

War time research (left to right) : SMA-3 pilot Aptitude test, Cambridge Cockpit, Mackworth Clock, Fighter Control Rooms, Bomb-aiming Apparatus

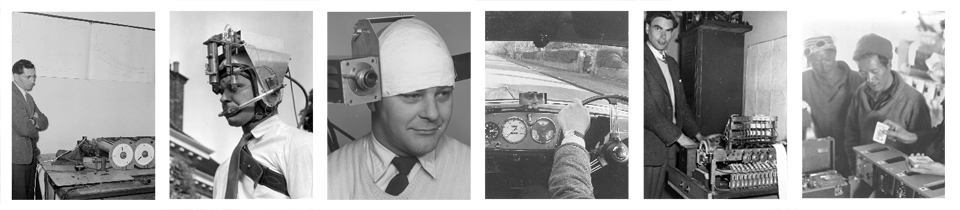

In response to the technological and human demands of the Second World War, the MRC capitalised on work they already funded in the Laboratory of Experimental Psychology in Cambridge and, in 1944, “a Unit for Research in Applied Psychology” was established within in the University. During this critical period, tests were developed to assess intelligence and sensory motor ability (e.g. SMA-3 pilot aptitude test illustrated above and now in the Science Museum in London) were developed for selecting people for various wartime roles. Some tests also measured “Temperament and Character” demonstrating an early concern with, among other individual differences, mental health issues such as neuroticism. The first flight simulator was created to study the effects of long flying hours and the Mackworth Clock test was developed to study, for example, the optimal periods over which submariner’s attention could be focussed on detecting intermittent sonar signals. The effects on behaviours of key drugs, gases, vitamin supplements, high temperatures and humidity were systematically evaluated. Problems of information display, the design of operator controls for complex equipment (including aiming and choice), as well pattern recognition (notably aircraft) all posed significant fundamental questions about biomechanics, human perception, attention and decision-making. Kenneth Craik, the Units’ first director was a pioneer in the use of computation as a theoretical model for human information processing, developing what was probably the very first computational model of skill and applying it to the wartime task of gun-aiming. The results of the whole research programme had very substantial effects on military practice and procedures, including the design of the famous control rooms for directing the Battle of Britain (illustrated above), changes in watch keeping routines, methods for testing equipment and, of course, measuring psychological profiles for selecting service personnel. The SMA-3 test shown above was in use in several national air forces until 1985 when it was finally replaced by a computerised version. With a concern for accident prevention, preliminary investigation of flying and mining accidents inspired new statistical methods. Extensive investigations were also carried out into methods to assist with the rehabilitation of hospital patients, including those with impaired sensory and motor systems, as well as prisoners of war.

The themes and approaches established during the War have many direct descendants and echoes across subsequent decades in which the directors who succeeded Kenneth Craik each tailored the topics of Unit research to the demands of their time.

Directors of the Unit

Unit Directors (left to right): Kenneth Craik, Sir Frederick Bartlett, Norman Mckworth, Donald Broadbent, Alan Baddeley, William Marslen-Wilson, Sue Gathercole)

The immediate post-war era

Craik was tragically killed in a cycling accident just as the war was ending and was succeeded by Sir Frederick Bartlett, who was also Professor within the University Department of Psychology at the time. He directed Unit research in an honorary capacity from 1945-1951. Bartlett had a great talent for combining careful experimentation with the development of theory that was applicable to naturalistic as well as experimental data. He and Norman Mackworth, who held the directorship from 1951 to 1958, gradually broadened the research to encompass a greater proportion of questions prompted by the civilian concerns of industrial production, transport and telecommunications. So, for example, the research thread for individual differences refocused on medical students, while new equipment and methods were developed for simulating complex industrial tasks such as those found in automated textile mills. These, and indeed any kind of machine room, are typically noisy places to work and it was in this post-war period that several of the unit’s classic research topics were initiated including studies of the effects of noisy environments and divided attention.

Once again new techniques and apparatus for measuring behaviour such as several simultaneously changing states, early forms of eye-tracking, the use of head-mounted video-cameras (now comically large) and instrumented cars were pioneered in this period. It is easy to forget in an age of computers and electronic tablets, that test apparatus required electrical and mechanical workshops and extraordinary innovation. In period, Richard Gregory, crafted an exquisitely complex multi-attribute measuring device named after the Greek god “Thor.” An electro-mechanical card-sorting apparatus built at the Unit even accompanied one expedition up Mount Everest in 1960-61 to assess the effects of reduced oxygen at altitude on human cognition.

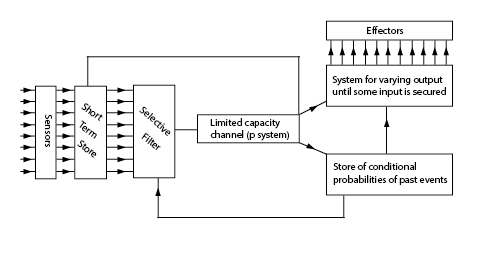

Broadbent’ 1958 filter model of limited storage and processing channels

As before the concern was not just with addressing questions that needed answering in the workplace. Systematic phenomena were being established that needed characterising and explaining. Information theory was evolving. In 1952 Hick developed one of the few law’s that have been generated in psychological science. Hick’s Law accurately captures the relationship between the number of choices among which a decision has to be made and the time it takes to make that choice. In this post-war period ideas about mental limitations were formulated in the language of communications channels. The principle that a person can only track a single stream of information at any given moment was crucial in Donald Broadbent’s formulation of mechanisms of attention, short term memory and cognition that would frame much of the Units research from the late 1950’s through to the 1970’s. Broadbent’s classic book Perception and Communication, published in 1958, was a major influence in the years that saw cognitive psychology become the dominant theoretical paradigm.

The research themes established during the war and immediately afterwards continued to be prominent in the new climate of cognitive psychology. The progress report from 1970 notes that work on work on signal detection, division of attention, motor performance, and effects of abnormal environments are still prominent but were now embedded in more diverse contacts with government organisations. Among those requesting research were the Post Office, the Transport and Road Research Laboratory, London Transport, the Decimal Currency Board, the Gas Board, the Home Office, and Cambridge Hospitals. But the challenges the concerns raised buy these departments once again led to new aspects of mind being investigated.

Circadian rhythms, sleep deprivation, the demands of learning, remembering and using postcodes and telephone numbers, distinguishing values of postage stamps by colour, or coinage by size, weight and shape; complex verbal or diagrammatic instruction all stimulated research, required new methods and led to theoretical innovation. Indeed, the 1970 progress report organised the way research was presented entirely in terms of Broadbent’s filter model. Many new phenomena were discovered and charted such as acoustic and semantic confusion in short- and long-term memory; different patterns in the recall of auditory and visually presented lists of words; difficulties perceiving words presented in noise; and the motor skill requirements of learning and using alphanumeric keyboards. Such phenomena helped frame cognitive theories of pre-categorical acoustic storage, sequentially ordered short- and long-term memory systems as well as theories of word recognition and decision-making. In spite of its modest size the Unit was starting to punch well above its weight on the international stage. Early research on deaf children and the declines in cognitive performance that accompany normal ageing also figure prominently in this period – a foretaste of our current emphasis with studying mind and brain across the lifespan. Our archive contains a charming film called “With People in Mind” made in 1971. This captures not only the essence of the research work, but like a time capsule, it also conveys a very strong sense of the historical era in which that research was carried out with its inherent context of fashion, technology and styles of communication expected of professional scientists in the public eye.

The unit acquired its first computer in 1970, it was a large, expensive and precious resource. Yet it had a tiny fraction of the storage and computational capability of one of today’s inexpensive smartphones. Its arrival heralded an era in which experimental methods for dealing with and measuring speech processing, language, memory, knowledge and reasoning could all be reshaped. New programming methods also meant that Craik’s early vision of computational theories of mind could now be pursued across the full range of mental faculties. Shortly afterwards in 1974, the new Director Alan Baddeley began recruiting a whole new generation of scientists trained not only in the methodologies of cognitive sciences but also those with expertise in neuropsychology, rehabilitation and clinically qualified experts in researching anxiety and depression. Over the next two decades there was a dramatic explosion of productivity in output.

Empirical paradigm development flourished across the range from simple laboratory tasks to assess fundamental aspects of perception, memory, attention, language and reasoning through to complex real world tasks of an information and knowledge intense age increasing dependent upon computer technologies. The real world tasks even extended to studies of the perceptual and motor skills of elite international sportsmen, the assessment of how evidence in intricate fraud trials might be understood (or not) by juries, and the effects of disguise on face recognition in public places. Past themes resurfaced in response to new circumstances. For example, the advent of North Sea oil revived diving research and the effects of breathing different mixes of gases required for installation and repair work at great depths were evaluated as were the effects of anaesthetic gases used in medical procedures on awareness and memory. Rather than symbols for tracking attacking and defending aircraft, international travel required traffic and public information signs all to appear in pictographic rather than verbal form and new research was required to evaluate the usability of complex pictorial instructions such as the use of payphones. Auditory warnings in civil aircraft and trains now signalled far more diverse information to crew than earlier detection tasks. Echoing the early development of intellectual and temperament assessment tests of the war years, new tests were developed for motor skills used in underwater manipulation, for balance, and for assessing numerous potential deficits in memory and language skills in adults and children.

There was equally vigorous diversification in theory development.

Alan Baddeley suceeded Donald Broadbent in 1974, and as Alan himself noted at the time, Donald would be a hard act to follow. Of course, Alan did follow that act with great distinction over the 22 years of his directorship. He ensured that core strengths in the major areas of cognitive psychology were maintained, while at the same time seeking areas of application that were tractable and fundable. With the increasing importance of computers in the workplace in the seventies and eighties, a larger part of the Unit’s work was conducted in association with industry, although this later diminished as recession affected industrial R&D budgets. In the beginning of the 1990’s health-related problems provided the major basis for applying and enriching cognitive psychology. Initial ventures in neuropsychology involved single case studies of patients with relatively pure and specific cognitive deficits. The field was developed to the point at which it could deal with a wider range of cases where the deficits are less specific. This in turn stimulated the new field of cognitive neuropsychiatry. Cognitive psychology was also extended to encompass the relationships between cognition and emotion, which became part of a vigorous area of interaction between academic and clinical researchers. A significant contribution towards blending theoretical and practical work was reflected in the neuropsychological rehabilitation group, which moved into its accommodation in Addenbrooke’s Hospital in 1995.

1994 was the CBU’s 50th anniversary year, and shortly after that anniversary, Alan Baddeley retired from the Directorship. He moved to Bristol University in September 1996 to focus on research related to his model of Working Memory. He subsequently moved to the University of York where he continues that work.

Women members of staff who rose to senior leadership roles at the CBU

Susan Gathercole  Emily Holmes  Dorothy Bishop  Karalyn Patterson  Ann Cutler  Barbara Wilson  Patrica Wright  Jane Mackworth  Maggie Vernon  Alice Heim

|

Shown here are some of our other female scientists who spent formative parts of their careers at the Unit and subsequently took on leadership roles elsewhere in psychology and neuroscience.

Sophie Scott  Nillie Lavie  Elizabeth Maylor  Judi Ellis  Judy Edworthy  Ruth Byrne  Vicky Bruce  Ann Blandford  Jackie Andrade  Hilary Buxton |

William Marslen-Wilson took up his appointment as the Director of the Unit in July 1997 with a new remit from the Medical Research Council. Under his guidance, the work of the Unit was refocused on the task of constructing explanatory theories of the major components of human cognitive function, marrying psychological and computational accounts of cognitive function and architecture with increasingly detailed analyses of how these functions are realised in the brain. In collaboration with the Department of Experimental Psychology, the Clinical School, the Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre, and other Cambridge-based programmes, the Unit’s current research is now aimed at a greater integration of cognitive science with neuroscience. To reflect these changes, the Unit was re-named the Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit (CBU) in April 1998.

As part of this process of change and renewal, the Unit also went through a major programme of remodelling and rebuilding. Along with the refurbishment of the old Edwardian mansion which forms the old heart of the Unit, the centrepiece of these developments was a new West Wing extension, opened in September 2001. This is a dramatic two-story addition to the CBU facilities, which houses extensive laboratory space for behavioural testing on the ground floor and excellent lecture theatre and seminar room facilities on the first floor. Beautifully integrated with the old house and with the CBU gardens (see photo at the top of this panel), this new building provides an appropriate setting for the Unit’s role as a major UK centre for 21st century interdisciplinary science .

Another exciting development was seen at the end of 2005, with the MRC investing around £1.7 million in the CBU’s future with the erection of a new building to house a 3 Tesla Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scanner on the premises. This facility is a valuable resource for the Unit and for others within the Cambridge imaging community.

2007 has seen a further major investment of £1.5 million by the MRC with the installation of a Magnetoencephalographic (MEG) facility on the premises. This will ensure that the Unit is able to maintain and build on its reputation as an internationally renowned centre for Neuroscience research. Again, this resource will also be used by other researchers in Cambridge.

Further details about these Research facilities, as well as the Research Programmes making use of them, can be accessed directly from the menu at the top left of this page.

MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit

MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit