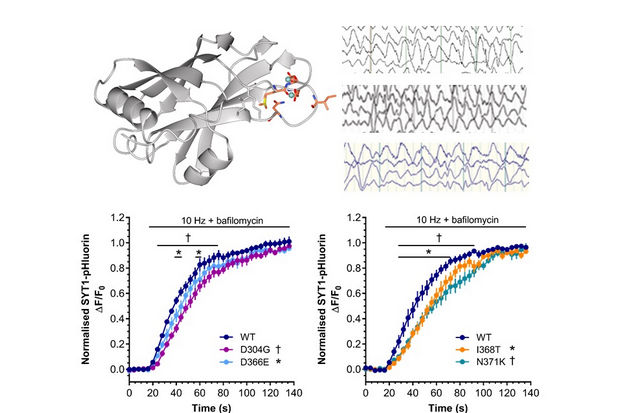

In 2015, Kate Baker and colleagues published the first report of a child with severe, complex disabilities and a variant in a gene called Synaptotagmin 1 (SYT1). SYT1 co-ordinates communication between brain cells by triggering the release of neurotransmitter-filled vesicles. Following this discovery, genomic testing laboratories around the world began to look for similar cases. By 2017, ten more cases of SYT1 variant had been identified worldwide. Most of these children do not use speech to communicate, spend a lot of time chewing their fingers, and are described as unpredictable, switching from calm to agitated for no obvious reason. Another striking similarity is an unusual pattern of brain electrical activity, not seen in other neurodevelopmental disorders.

To understand how SYT1 variants affect brain function to cause this spectrum of problems, Kate teamed up with Sarah Gordon, a synaptic physiologist at the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health in Australia. Sarah’s team found that the SYT1 variants identified in patients affect brain cells by slowing down vesicle release in response to electrical activity. We now hope to understand how SYT1 variants and neurotransmission speed influence cognitive development, leading to the symptoms experienced by patients. The ultimate goal is to discover safe and effective therapies to improve quality of life for children and adults with SYT1 variants.

Baker K, Gordon SL, Melland H, et al. SYT1-associated neurodevelopmental disorder: a case series. Brain. 2018;141(9):2576-2591. doi:10.1093/brain/awy209

MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit

MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit